In the blandly named Autobiography of a Chinese Woman (1947), Yang Buwei begins by declaring that she is a “typical Chinese woman” who is married and has “four children, a very typical number for a Chinese woman to have”; she acknowledges that she has “such an amount of vanity as becomes [her] sex” (3). Yet, the subsequent pages would suggest that she is anything but a typical person, Chinese, woman, or otherwise. Yang was born in 1889 and came of age during the transition from late-Qing to Republican China. Her résumé during the 1910s to the 1920s is astounding: she was an anti-Qing revolutionary with Sun Yat-sen’s Tongmenghui, one of the earliest Chinese women trained in science-based medicine, and the co-founder of a women’s hospital in Beijing (B. Y. Chao 36; 118–228). After migrating to the U.S. around 1938, she published the cookbook, How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (1945), which stoked American interests in Chinese cuisine (Coe 218–20). It is now widely credited for coining the neologisms “stir-fry” and “potsticker” (“Stir-Fry, n.”; “Potsticker, n.”). In her time, Yang was a trailblazer who exemplified the May Fourth spirit of women’s emancipation in modern China, in the face of numerous crises such as the Second Revolution of 1913, the 1918 flu pandemic, the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937, and the advent of the Asia-Pacific Cold War around 1949. In our time, her autobiography offers hope that feminist commitments and cosmopolitanism can prevail in a world fractured by COVID-19 and intensifying Sino-American tensions.

Portrait of Yang Buwei (left) as a young woman. Photograph courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

Portrait of Yang Buwei (left) as a young woman. Photograph courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

Despite her accomplishments, Yang adopts a “modest” narrating voice in her autobiography in two senses of the term. Her narration is often humble to the point of self-deprecation, and she relates her involvement in historical events in a non-epic fashion. Consider her self-portrayals: in a chapter titled “Sitting out the Revolution,” Yang reveals that during the Wuchang Uprising of 1911 which toppled the Qing dynasty, she and her brothers (cross-dressed as nuns) escaped by train to the foreign concessions of Shanghai. During the May Fourth Movement of 1919, Yang was studying at the Tokyo Women’s Medical College; she admits to sitting out on patriotic activities because she was focusing on completing her degree (144–45). During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Yang fled to the U. S. with her family, which led to her husband’s characterisation of themselves as “second-class Chinese [who] went abroad when they could and sat out the war in safety and comfort” (290). These accounts of her less-heroic moments are matched with a restrained writing style that does not draw attention to its own literariness. The organisation of her autobiography suggests that it was written in small snatches and designed to be read thus. The work is split into six parts, each containing around ten chapters spanning three to eight pages long. In terms of expression, Yang prioritises clarity and flow by using simple words and short sentences.

Yang’s modesties might have contributed to her obscurity today; in contrast, her husband, the prominent linguist Yuen Ren Chao, is routinely mentioned in studies of modern Chinese history [1]

. However, Yang’s modesties are also what make her work exceptional. They make her account of modern Chinese history accessible to foreign readers, and they represent her negotiations with the social pressures exerted on Chinese women writers.

Yang Buwei with her husband, Yuen Ren Chao, 1922. Photograph courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

Yang Buwei with her husband, Yuen Ren Chao, 1922. Photograph courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

The book’s foreword offers a glimpse into the thinking behind Yang’s modest prose and demonstrates the work’s understated artfulness. In four-and-a-half pages, it situates the

text within Chinese literary history, explains Yang’s writing process, and establishes the couple’s status as Chinese-American literati, all while injecting a hearty dose of comedy. Chao the husband begins with the following line: “Since my wife has the last word, I shall have the foreword” (vii). He explains that Yang’s autobiography owes a debt to Hu Shih’s call for a Chinese literary revolution in 1917—known also as the New Culture Movement—which made “writing in the vernacular respectable”; Yang can thereafter “take courage in writing as she talks” and “even feel fashionable about it” (vii–viii). Hu Shih was a family friend of the Chaos; his own autobiography, Sishi Zishu (Self-Narration at Forty, 1933), is often considered the model for modern Chinese autobiographies (Wang 33–34). Following Chao’s cerebral opening, Yang barges her way into the foreword by correcting him on various facts:

It was only eight months ago that she really got started—

No, Yuenren, you are all mixed up. You started with the English version eight months ago. I started with my Chinese a year ago—

You are right, Yunch’ing, you started a year ago [2]. Well, one day, while my wife was visiting New York, Pearl Buck suggested to her the idea of writing a short—

You are wrong there again, Yuenren. I did not see Pearl Buck on that occasion. It was Mrs. Lin Yutang who told me that Pearl Buck had asked her if she might—

But darling, is this your foreword or mine? If you keep interrupting—

Why not make it both yours and mine?—

That’s an idea, too. Suppose you go on from here, Yunch’ing!— (viii)

Yang’s interjections add levity by puncturing Chao’s academicism with a squabble. They casually namedrop Lin and Buck, signalling their membership in the elite circles of American letters; in fact, the autobiography was first published by the John Day Company, which was founded by Buck’s husband, Richard Walsh. This staged quarrel between husband and wife deftly positions Yang’s work at the intersection of Chinese and American literature.

Yang then explains that she prefers simple and direct writing over Chao’s literary pretensions, while also revealing that the English text was co-produced by the couple. She wrote first in Chinese, in a “straightforward way … [which keeps] the announcement of the outcome at the beginning of a story” (x–xi). The plan was for Chao to translate her “simple Chinese into Basic English” (x). “Basic English” refers to a system of 850 words devised by C. K. Ogden, which was primarily meant for teaching the language to children and second-language users (Ogden 221). However, Yang complains that her husband was not always “a well-behaved translator” (x). The linguistics professor “likes to indulge in verbal paradoxes,” prefers an “academic style of involved qualifications,” and occasionally renders her words into something “deep and abstract” (x). In various places, he attempts what he calls “fictional technique” where he “changed things around, so that the outcome of an incident will be delayed until the end” (x). Yang’s finger-wagging at her husband’s transgressions is accompanied by a caricature of herself as a nagging wife: “I have tried to catch him doing these things and registered my protests in the form of footnotes, but I won’t guarantee that I have not let some slip by” (x). Given that her work was published during the post-war era, a period haunted by the spectre of Communist China, Yang’s uses of humour and simple prose should be understood as strategic choices. Her tactics position the autobiography as non-threatening, middlebrow literature, such that its sympathetic account of modern Chinese history reaches the widest possible anglophone readership. While the couple ultimately discarded the idea of translating Yang’s Chinese prose into Basic English, this factoid discloses their ambitions for an autobiography that is simple enough to be read by second-language users of English. In other words, the modesties of Yang’s prose belie the size of her target readership.

A further explanation for Yang’s affectations of modesty can be found in Jing M. Wang’s When “I” Was Born, (2008), which explains that there was a cultural inhibition against self-narration in the Chinese literary tradition for both men and women (21). While there were pre-modern examples of women’s biographies, these were mainly demonstrations of women’s virtues (starting from the Han dynasty) or private eulogies for mothers written by sons (prevalent in the Qing era) (Wang 18–20). The contemporary understanding of the autobiography—a book-length work dedicated to its author’s views and experiences—was a relatively alien concept during the earlier decades of twentieth-century China, one which appeared egocentric and self-aggrandising to Chinese sensibilities. Wang’s research reveals that women writers such as Lu Yin and Su Xuelin struggled with abortive attempts at writing autobiographies, for fear of exposing themselves to ridicule (106; 120–21). In 1936, Lin Yutang contrasts the modesties of the Chinese against the immodesties of Western life writing:

The average intelligent man in the West is led to believe that if he only says what he has to say, there is a chance of selling his goods … Henry Ford, too, takes it upon himself to write about his own life … We have no Henry Fords in China, but even if we had, a Chinese Henry Ford would not dream of writing his own life. (235)

Lin’s sarcastic comments reveal how life writing, so prevalent in the West, is seen by the Chinese as a vulgar genre associated with individualism, self-promotion, and capitalism after Ford.

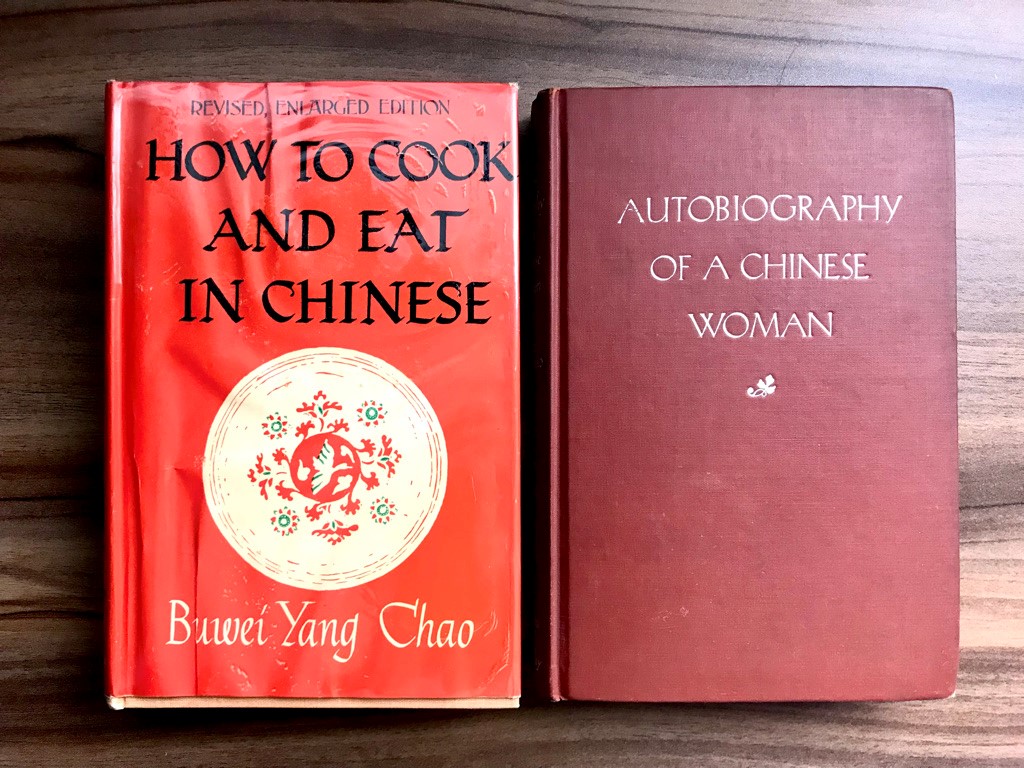

Yang Buwei’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (first published in 1945) and Autobiography of a Chinese Woman (1947).

Yang Buwei’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (first published in 1945) and Autobiography of a Chinese Woman (1947).

Given this context, it is not surprising that women autobiographers like Yang took on affectations of modesty to avoid reprisal while pushing at the boundaries of Chinese letters and manners. Their preference for simple, declarative writing, and their attention to world historical events and political developments over and above their own achievements, also cleave to the New Culture ethos of writing accessible literature, in the vernacular, for the masses. Yang’s husband and co-translator, Chao, was a leader of the New Culture Movement, though he was too modest to mention this in his wife’s work. Among other things, he sat on the national committee that standardised the Chinese vernacular and promoted its use as lingua franca (Zhong 37–41). In a 1916 manifesto that he co-authored in English with Hu Shih, Chao argues for a simplified style of writing in Chinese letters:

Allusions and quotations should not be multiplied unless calculated to mystify or to show off … We should avoid machinelike symmetry and antithethses [sic] at the expense of spontaneity and genuineness … Our letters should be freed from their “polite” nonsenses to give room for sincerity. Relatives and friends should write as they would talk … An extra page or two of formalities not only wastes time, energy and money, but it wastes attention and interest, and, as we say … puts a film between you and me. (Y. R. Chao 579–80)

Over three decades later, Yang’s autobiography would exemplify these demotic ideals in simple English.

Yang’s modest prose influenced my own expositional style, which strives to make literary scholarship engaging and accessible to a wider audience, while also spotlighting obscure women writers whose modesties may have caused their life and work to be overlooked by scholars today. My stance is aligned with what Jeffrey Williams calls “The New Modesty in Literary Criticism” (2015), which describes a recent turn towards “methods with less grand speculation”; its proponents “aim to read, describe, and mine data rather than make ‘interventions’ of world-historical importance” (par. 3). This turn is, in part, a return to more historically grounded scholarship, which had been edged out by the “theory generation” of the seventies to eighties (Williams par. 24–26). But the lessons that can be gleaned from more modest methods, and specifically, from “just reading” Yang’s autobiography, can be quite rewarding. Our protagonist mourned the deaths of relatives and friends caused by smallpox, typhoid, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, and the 1918 pandemic; these tragedies ignited her passion for internal medicine (

B.Y. Chao 146). Following her graduation from medical school, Yang had her career shunted by sexist governmental policies and was forced to serve as a gynaecologist and obstetrician (146). Despite this setback, she emerged as a birth control pioneer, inspired by the work of the American nurse Margaret Sanger. In 1924, Yang translated Sanger’s women’s health manual, What Every Girl Should Know (1916), into Chinese, and founded a birth control clinic the following year (

B.Y. Chao 210; 228 ). After her migration to the U. S., Yang continued to push for transnational understanding and collaboration by writing a cookbook and an autobiography in English, both of which introduced Chinese culture and history to anglophone readers within and beyond the U. S. In an era afflicted by yet another pandemic, travesties that prompted social movements like #metoo and #stopasianhate, and deepening fault lines between China and the U. S., Yang’s story offers both consolation and inspiration that one’s modest struggles against the forces of history can yield surprising results.

In the famous essay “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism” (1986), Fredric Jameson describes Lu Xun’s magisterial refusal of medicine for literature:

Lu Xun decided to study western medicine in Japan—the epitome of some new western science that promised collective regeneration—only later to decide that the production of culture—I am tempted to say, the elaboration of a political culture—was a more effective form of political medicine. (73)

Unlike her contemporary Lu Xun, Yang was not a writer of high literature; however, she embraced both medicine and literature by putting May Fourth ideals of women’s emancipation into practice through her birth control advocacy, and by producing accessible writing about China for international readers. As Richard Jean So might have it, Yang was part of a transpacific cultural network, developed between the First World War and the late forties, that facilitated “East-West cultural relations that operate[d] through reciprocal interaction rather than hegemony” (XIII–VI). Her example enables the imagination of a world connected by intellectual exchanges rather than one separated by geopolitical rivalries. I am reminded of this whenever I sit down to a humble plate of stir-fried tofu or pot stickers.

Footnotes

[1]See Yurou Zhong’s Chinese Grammatology (2019) for a recent appraisal of Chao’s work.

[2]“Yunch’ing” is one of Yang’s monikers.

Works Cited

Chao, Buwei Yang. Autobiography of a Chinese Woman: Put into English by Her Husband Yuenren Chao. John Day Company, 1947.

Chao, Yuen Ren. “The Problem of the Chinese Language: IV. Proposed Reforms.” The Chinese Students’ Monthly, vol. 11, no. 8, 1916, pp. 572–93.

Coe, Andrew. Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Jameson, Fredric. “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism.” Social Text, no. 15, 1986, pp. 65–88.

Lin Yutang. “Contemporary Chinese Periodical Literature.” T’ien Hsia Monthly, vol. 2, no. 3, 1936, pp. 225–44.

Ogden, C. K. “Round the Earth with 850 Words.” The Vocational Guidance Magazine, vol. 13, no. 3, Dec. 1934, pp. 220–22.

“Potsticker, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press. Oxford English Dictionary, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/261509. Accessed 13 Aug. 2021.

So, Richard Jean. Transpacific Community: America, China and the Rise and Fall of a Cultural Network. Columbia University Press, 2016.

“Stir-Fry, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press. Oxford English Dictionary, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/34933688. Accessed 13 Aug. 2021.

Wang, Jing M. When ‘I’ Was Born: Women’s Autobiography in Modern China. University of Wisconsin Press, 2008.

Williams, Jeffrey J. ‘The New Modesty in Literary Criticism’. The Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 61, no. 17, https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-new-modesty-in-literary-criticism/.

Zhong, Yurou. Chinese Grammatology: Script Revolution and Chinese Literary Modernity, 1916-1958. Columbia University Press, 2019.