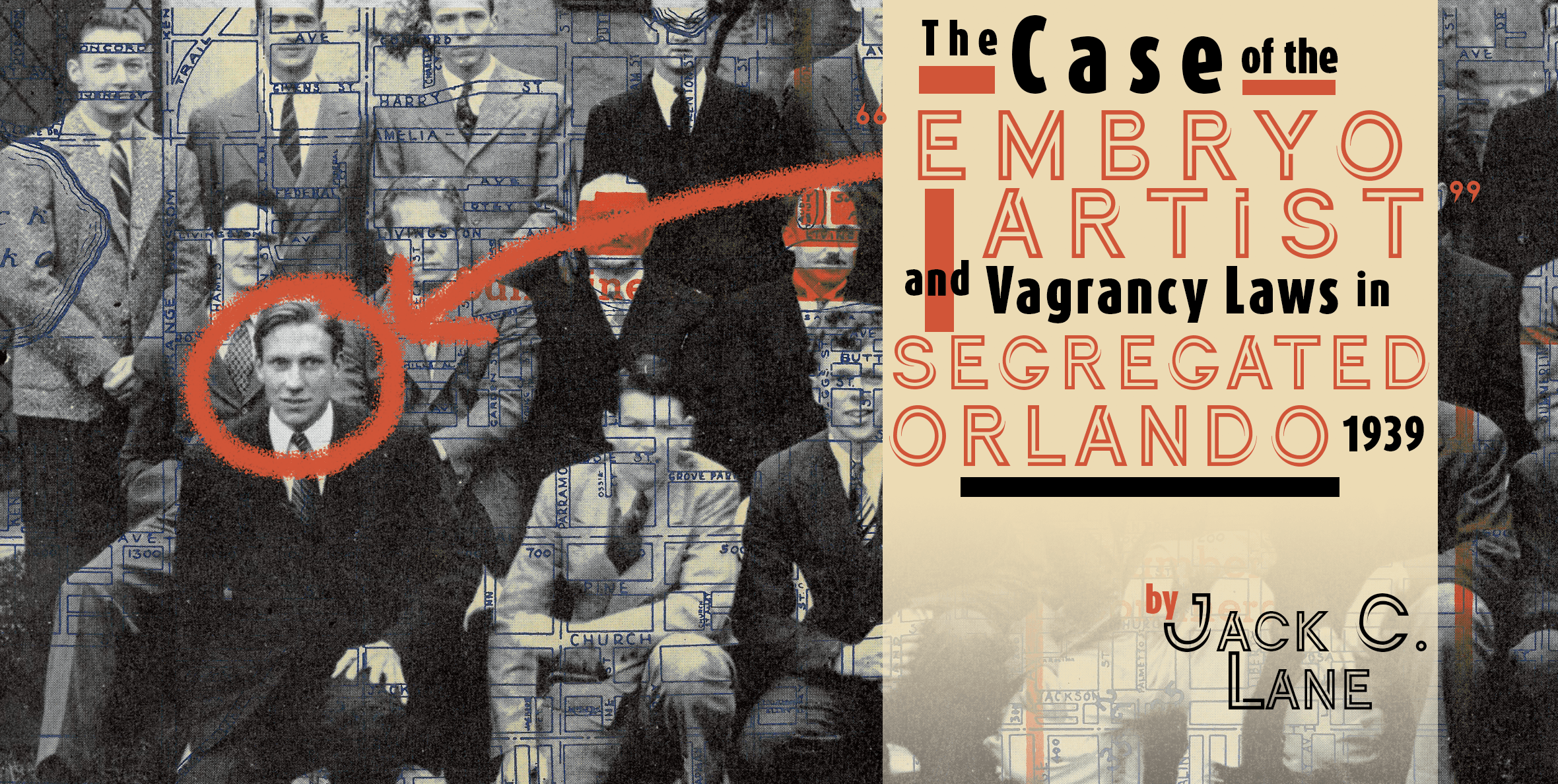

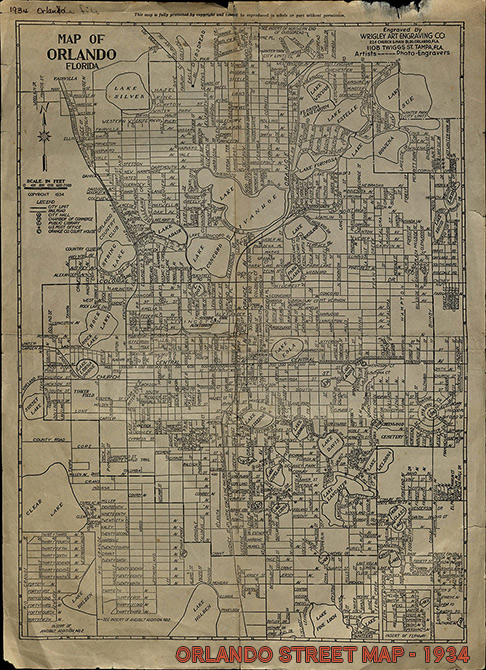

![]() he setting: a warm Saturday evening in June 1939; the place: the Parramore district on the west side of the city of Orlando, Florida, a neighborhood established in the 1880s “to house blacks employed in the households of Orlando.” Over the following decades, the neighborhood not only grew in size but also evolved as a thoroughly segregated section of the city. It was separated from the east side white section by (appropriately named) Division Street.

he setting: a warm Saturday evening in June 1939; the place: the Parramore district on the west side of the city of Orlando, Florida, a neighborhood established in the 1880s “to house blacks employed in the households of Orlando.” Over the following decades, the neighborhood not only grew in size but also evolved as a thoroughly segregated section of the city. It was separated from the east side white section by (appropriately named) Division Street.  In 1939, there was a common understanding enforced by the police department that neither blacks nor whites could cross Division Street after sundown.

In 1939, there was a common understanding enforced by the police department that neither blacks nor whites could cross Division Street after sundown.

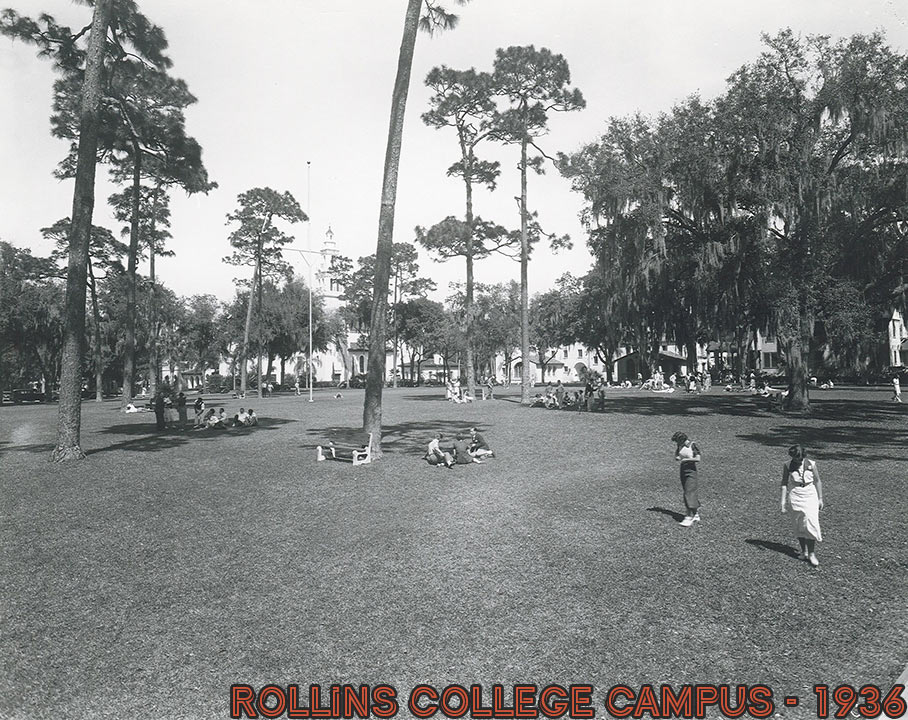

Ignorant of or choosing to ignore this convention, two young white students, enrolled at nearby Rollins College, decided to cruise in the Parramore neighborhood to gather, they said, material for a short story on African-American street life. As they crossed Division Street, they saw a police car with flashing lights stopped in front of a local bar. The two students exited their car and stood on the opposite side of the street watching the policemen confront a group of African American males.

Ignorant of or choosing to ignore this convention, two young white students, enrolled at nearby Rollins College, decided to cruise in the Parramore neighborhood to gather, they said, material for a short story on African-American street life. As they crossed Division Street, they saw a police car with flashing lights stopped in front of a local bar. The two students exited their car and stood on the opposite side of the street watching the policemen confront a group of African American males.  When Officer C.C. Phelps spotted the two boys, he walked across the street and “roughly” ordered them to leave. One of the boys demanded to know what law they had broken by peacefully standing on the sidewalk. An argument ensued. The most vocal and most defiant young student was charged with vagrancy and taken to the city jail.

When Officer C.C. Phelps spotted the two boys, he walked across the street and “roughly” ordered them to leave. One of the boys demanded to know what law they had broken by peacefully standing on the sidewalk. An argument ensued. The most vocal and most defiant young student was charged with vagrancy and taken to the city jail.

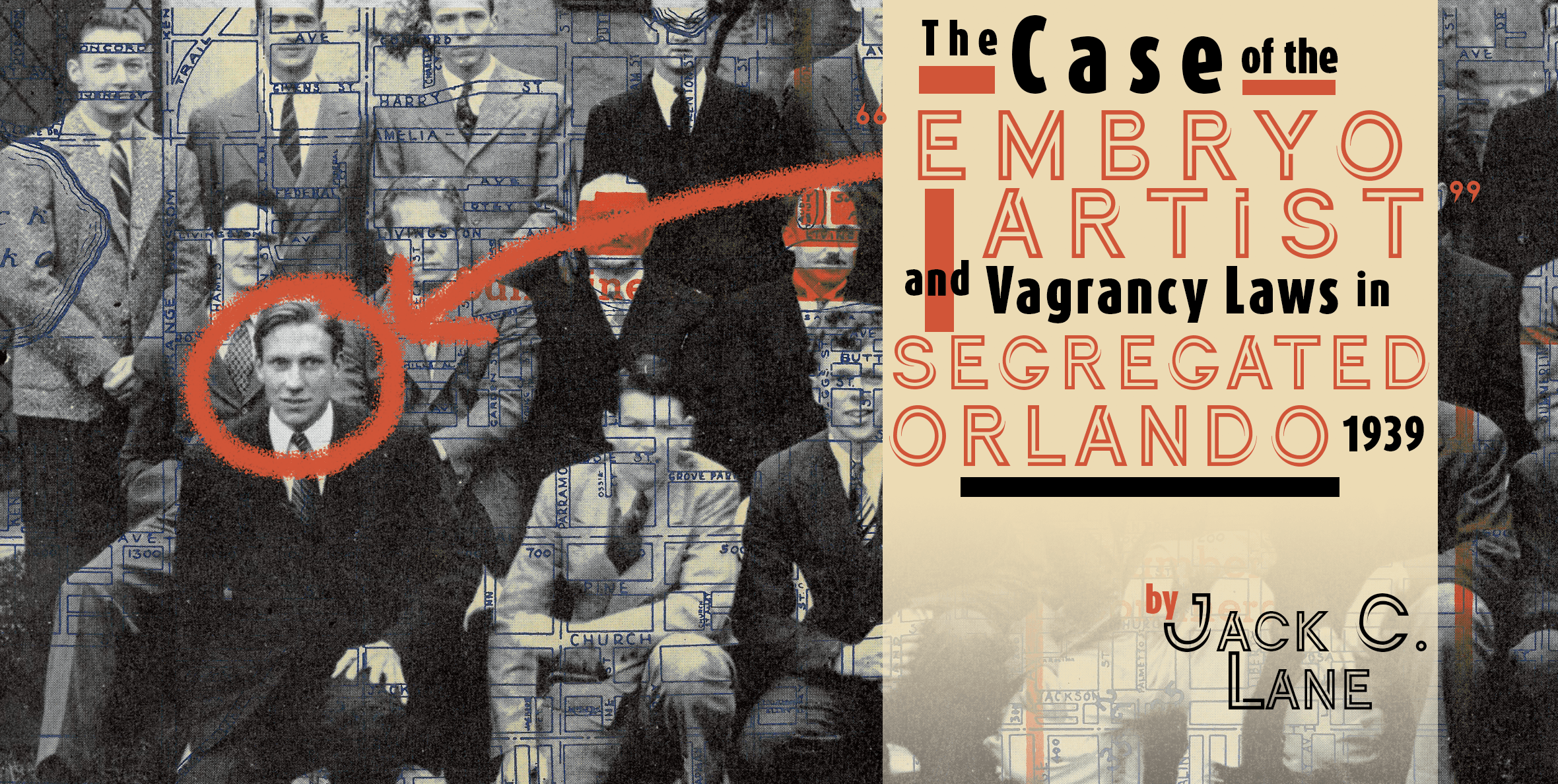

The following morning, readers awoke to these headlines on the front page of the Orlando Sentinel:

EMBRYO ARTIST IN TROUBLE

YOUNG AUTHOR FINED ON VAGRANCY CHARGES;

YOUTH FOUND IN NEGRO SECTION

Central Floridians may have been surprised to learn the police had arrested a white “embryo artist” for vagrancy but for African Americans in Orlando’s “colored district” such arrests were all too frequent. Vagrancy laws, common in all the states, historically were used to rid roads and streets of what society considered undesirables—tramps, unemployed, homeless, etc. After the Civil War Southern States found them particularly useful as a way to control wandering freed slaves. These laws became an essential feature of the restrictive Black Codes and as these codes morphed into the Jim Crow segregation system, vagrancy laws became indispensable tools for maintaining the physical separation of the races.

Florida’s law, enacted in 1907 and still enforced in 1939, was written vaguely enough to allow police officers to use wide discretion in determining whom and when to arrest for vagrancy. It included these violations:

![]() rmed with this roving, sweeping authorization, Orlando police officers possessed virtually unlimited authority when patrolling the “colored section” of Orlando. In the Parramore neighborhood, African Americans could be told to “move on” merely for standing on sidewalks. Any resistance meant arrest. The case was usually adjudicated by the police chief and with only the accused’s word against a police officer, an African American had no hope of due process. Most spent a night or even days in jail because they could not pay the fine. Under these circumstances, often the only offense committed by a defendant was his blackness.

rmed with this roving, sweeping authorization, Orlando police officers possessed virtually unlimited authority when patrolling the “colored section” of Orlando. In the Parramore neighborhood, African Americans could be told to “move on” merely for standing on sidewalks. Any resistance meant arrest. The case was usually adjudicated by the police chief and with only the accused’s word against a police officer, an African American had no hope of due process. Most spent a night or even days in jail because they could not pay the fine. Under these circumstances, often the only offense committed by a defendant was his blackness.

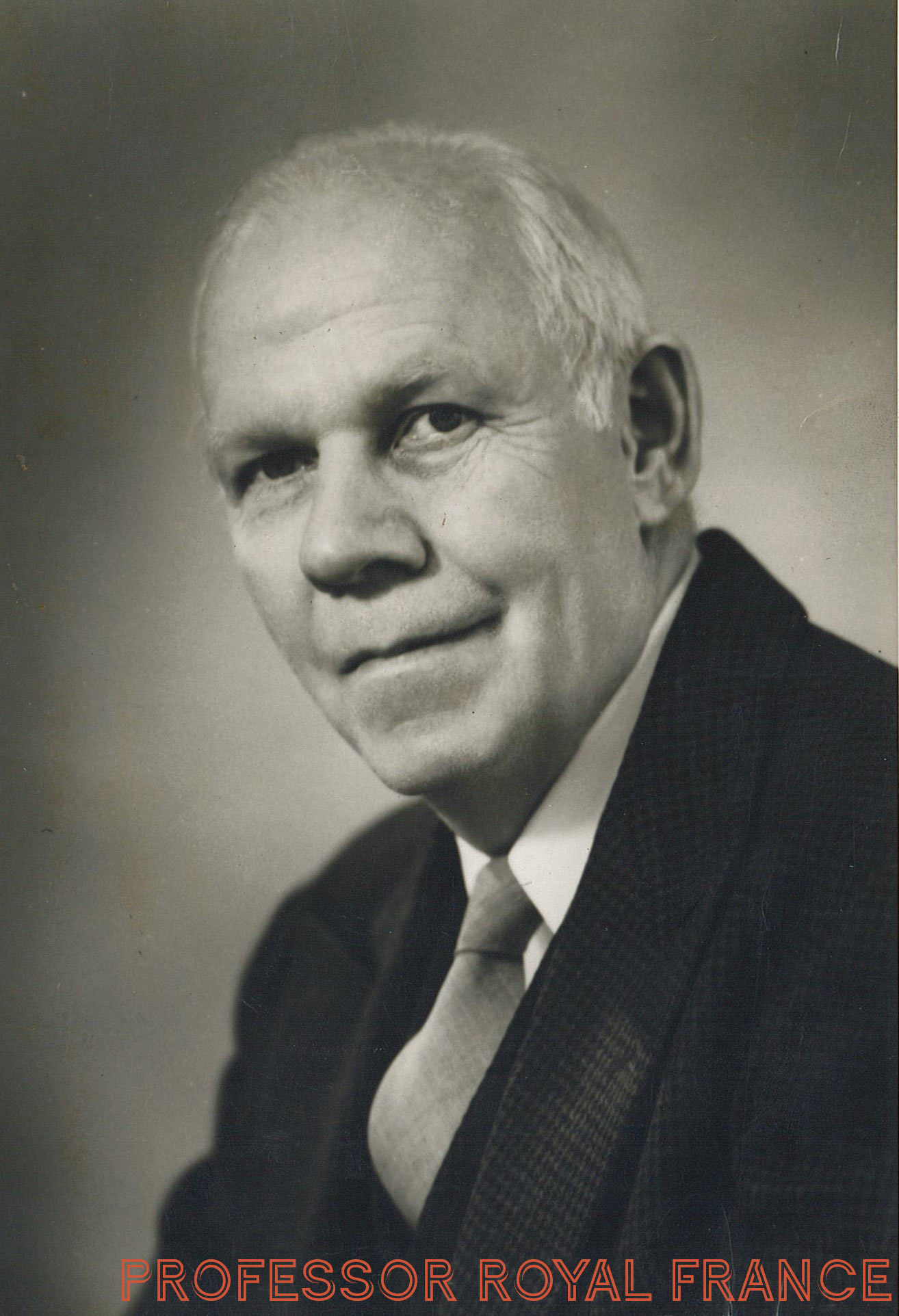

The two young Rollins College students were observing such an incident when one of them was arrested for vagrancy. The incarceration of white affluent male in Orlando on vagrancy charges was virtually unheard of; in the case of a young Rollins student it was also problematic. For that student, Harold Boyd France, was the son of Rollins College Professor Royal France.  Professor France was well known throughout Central Florida for his radical activism (he was president of the Florida Socialist Party), for his vocal opposition of the segregation system and of police brutality against African Americans. He purposely flaunted southern sensibilities and mores by refusing to call African-Americans by their first names (using Mr. and Mrs. instead), by frequently attending Sunday services at one of the churches in the Hannibal section of Winter Park and by often entertaining Eatonville’s noted African-American writer, Zora Neale Hurston, in his home on Osceola St.

Professor France was well known throughout Central Florida for his radical activism (he was president of the Florida Socialist Party), for his vocal opposition of the segregation system and of police brutality against African Americans. He purposely flaunted southern sensibilities and mores by refusing to call African-Americans by their first names (using Mr. and Mrs. instead), by frequently attending Sunday services at one of the churches in the Hannibal section of Winter Park and by often entertaining Eatonville’s noted African-American writer, Zora Neale Hurston, in his home on Osceola St.

As soon as he learned of his son’s arrest, Professor France hurried to the Orlando police station and stormed into the Chief of Police’s office demanding to know why his son was arrested for standing peacefully on the sidewalk. Chief of Police Billy Smith told him “the negro section was no place for [a white youth], especially on Saturday night and especially in view of the trouble the police had been having with the blacks recently.” Although unconvinced of this claim, France paid the bond and the Chief released his son. Before leaving, France delivered a withering verbal attack on Chief Smith and the Orlando police. It was precisely this kind of behavior, France told the chief, that was giving the Orlando police a bad name and he intended to sue the department for false arrest. Unimpressed by this threat, Smith replied with obvious contempt, “When you sue you better sue for a lot of money because we don’t like to fool with small damage suits.”

![]() his contentious encounter between a Rollins College professor and the Orlando Chief of Police has its interesting and revealing aspects. Only a well-connected white person would have dared speak to a police chief in those words and tone.

his contentious encounter between a Rollins College professor and the Orlando Chief of Police has its interesting and revealing aspects. Only a well-connected white person would have dared speak to a police chief in those words and tone.  Had an African American father been so foolish as to barge in to complain about his son’s arrest, he would never have made it to the Chief’s office because, at the very least, he probably would have been thrown in jail himself. It was dangerous for a black person to confront a white policeman anywhere, much less at a police station. This encounter also provides us an insight into the white consensus supporting the segregation system in Orlando. Chief Smith felt unmistakably secure treating France’s accusations in such a condescending almost scornful manner. He knew he had the majority white community behind him. In the 1930s, policemen in Orlando, and throughout Florida for that matter, were given carte blanche to keep African Americans confined in the segregation system. Only after his own son’s arrest did an outspoken civil rights activist such as Royal France make a complaint. Significantly, while his son’s arrest made the front pages of the local newspaper, the arrest of countless African Americans for vagrancy would never be considered newsworthy.

Had an African American father been so foolish as to barge in to complain about his son’s arrest, he would never have made it to the Chief’s office because, at the very least, he probably would have been thrown in jail himself. It was dangerous for a black person to confront a white policeman anywhere, much less at a police station. This encounter also provides us an insight into the white consensus supporting the segregation system in Orlando. Chief Smith felt unmistakably secure treating France’s accusations in such a condescending almost scornful manner. He knew he had the majority white community behind him. In the 1930s, policemen in Orlando, and throughout Florida for that matter, were given carte blanche to keep African Americans confined in the segregation system. Only after his own son’s arrest did an outspoken civil rights activist such as Royal France make a complaint. Significantly, while his son’s arrest made the front pages of the local newspaper, the arrest of countless African Americans for vagrancy would never be considered newsworthy.

As evidence of the white consensus around segregation, an editorial appeared in the Orlando Sentinel two days after Boyd France’s arrest. Entitled “A Practical Matter,” the editorial expressed full support for the Chief of Police. “Constitutional rights are fine things,” editor Martin Andersen observed, “but they won’t keep you out of trouble or repair broken skulls. Mr. Harold Boyd France was lucky to get arrested Saturday night when he was loitering around Orlando’s negro section looking for color to build into a short story. Many things might have happened if he hadn’t tangled with the police officer. [That is why] Chief Billy Smith has a philosophy about the situation we think is about right. Negroes belong in negro town after dark and whites should stay out. The police have been doing a good job guiding negroes to better citizenry. We feel the smartest and safest thing the rest of us can do is to help our police do their job. It may be hard on literary efforts,” the editor noted sarcastically, “but it’s better for the rest of us.”

For a civil rights activist like Royal France, this kind of police arrogance sanctioned by the city’s newspaper editor could not go unchallenged. Convinced vagrancy laws violated the Bill of Rights, France decided to use his son’s arrest as an opportunity to involve the Department of Justice in a case that could have national implications. He began by writing a letter to Chief Smith in which he contested the Chief’s and the Sentinel’s claim that Officer Phelps arrested his son from concern for his safety. He took issue with the “theory that a white man is not safe in a Negro section [of Orlando].  I believe that few if any Negroes would raise a hand against a white man in this country unless under extreme provocation.“ The “safety” theory, France implied, was not a reason but an excuse, the kind of pretense commonly used to intimidate African Americans. Any citizen, France lectured Chief of Police Smith, had the right to be on “any street in the City of Orlando so long as he was not obstructing traffic or conducting himself in any unlawful manner.” His son had politely “asked Officer Phelps a perfectly proper question as what law he was violating. [Phelps should] have answered the question in a courteous way. Instead, so high and mighty did he evidently feel himself that any questioning of his authority seemed to him belligerent. He became abusive and talked about a ‘smart guy” and [told my son] ’you ought to have the s**t kicked out of you.” France thought he knew why such abusive behavior by Phelps and other officers had become typical practice of the Orlando police force. They were following the example of their chief: “I doubt whether a Chief of Police who speaks scornfully of ‘n****rs and n****rtown’ is in a position to get the best results in law enforcement among the colored section of our population” France then warned Chief Smith that he would be taking action against the department for the “unlawful arrest” of his son.

I believe that few if any Negroes would raise a hand against a white man in this country unless under extreme provocation.“ The “safety” theory, France implied, was not a reason but an excuse, the kind of pretense commonly used to intimidate African Americans. Any citizen, France lectured Chief of Police Smith, had the right to be on “any street in the City of Orlando so long as he was not obstructing traffic or conducting himself in any unlawful manner.” His son had politely “asked Officer Phelps a perfectly proper question as what law he was violating. [Phelps should] have answered the question in a courteous way. Instead, so high and mighty did he evidently feel himself that any questioning of his authority seemed to him belligerent. He became abusive and talked about a ‘smart guy” and [told my son] ’you ought to have the s**t kicked out of you.” France thought he knew why such abusive behavior by Phelps and other officers had become typical practice of the Orlando police force. They were following the example of their chief: “I doubt whether a Chief of Police who speaks scornfully of ‘n****rs and n****rtown’ is in a position to get the best results in law enforcement among the colored section of our population” France then warned Chief Smith that he would be taking action against the department for the “unlawful arrest” of his son.

France was emboldened to “take action” at this time because recently he had learned that US Attorney General Frank Murphy had created a new Civil Rights Unit specifically devoted to protecting civil liberties and presumably to prosecuting violations of those rights. Likewise, France had read a recent federal court decision that declared the streets of a city belonged to the public, that people had a right to use the streets for talking with each other and exchanging ideas. He concluded therefore that the federal courts and the Justice Department were prepared to take action against laws giving local police sweeping powers to interfere with people’s rights peacefully to use the streets.

![]() n June 26, 1939, he wrote a letter directly to US Attorney-General Frank Murphy where he quoted at length excerpts from a speech Murphy had delivered concerning local civil rights transgressions. France reminded Murphy of his remarks: “We hear of municipal officials aiding in the provocation of race conflict, even though government in a democracy is intended to be for all not just some of the people. We hear of arbitrary ordinances and arbitrary police actions. But there is no need to look to the Department of Justice for proof. The citizen who looks carefully can see all around him the discrimination practiced against those who happen to be born with a darker skin than most people possess.” France informed Murphy that his son had recently been the victim of an “arbitrary and lawless kind of police action in Orlando Florida to which you refer. He was arrested under a [vagrancy] ordinance that the federal courts had determined indicated violated the Bill of Rights.” Under the Orlando ordinance, France explained, “a white person may be arrested for being in a negro section and a negro may be arrested for standing peacefully on the street if a policeman tells him to move on.” He pleaded for the Department to investigate his son’s unlawful arrest.

n June 26, 1939, he wrote a letter directly to US Attorney-General Frank Murphy where he quoted at length excerpts from a speech Murphy had delivered concerning local civil rights transgressions. France reminded Murphy of his remarks: “We hear of municipal officials aiding in the provocation of race conflict, even though government in a democracy is intended to be for all not just some of the people. We hear of arbitrary ordinances and arbitrary police actions. But there is no need to look to the Department of Justice for proof. The citizen who looks carefully can see all around him the discrimination practiced against those who happen to be born with a darker skin than most people possess.” France informed Murphy that his son had recently been the victim of an “arbitrary and lawless kind of police action in Orlando Florida to which you refer. He was arrested under a [vagrancy] ordinance that the federal courts had determined indicated violated the Bill of Rights.” Under the Orlando ordinance, France explained, “a white person may be arrested for being in a negro section and a negro may be arrested for standing peacefully on the street if a policeman tells him to move on.” He pleaded for the Department to investigate his son’s unlawful arrest.

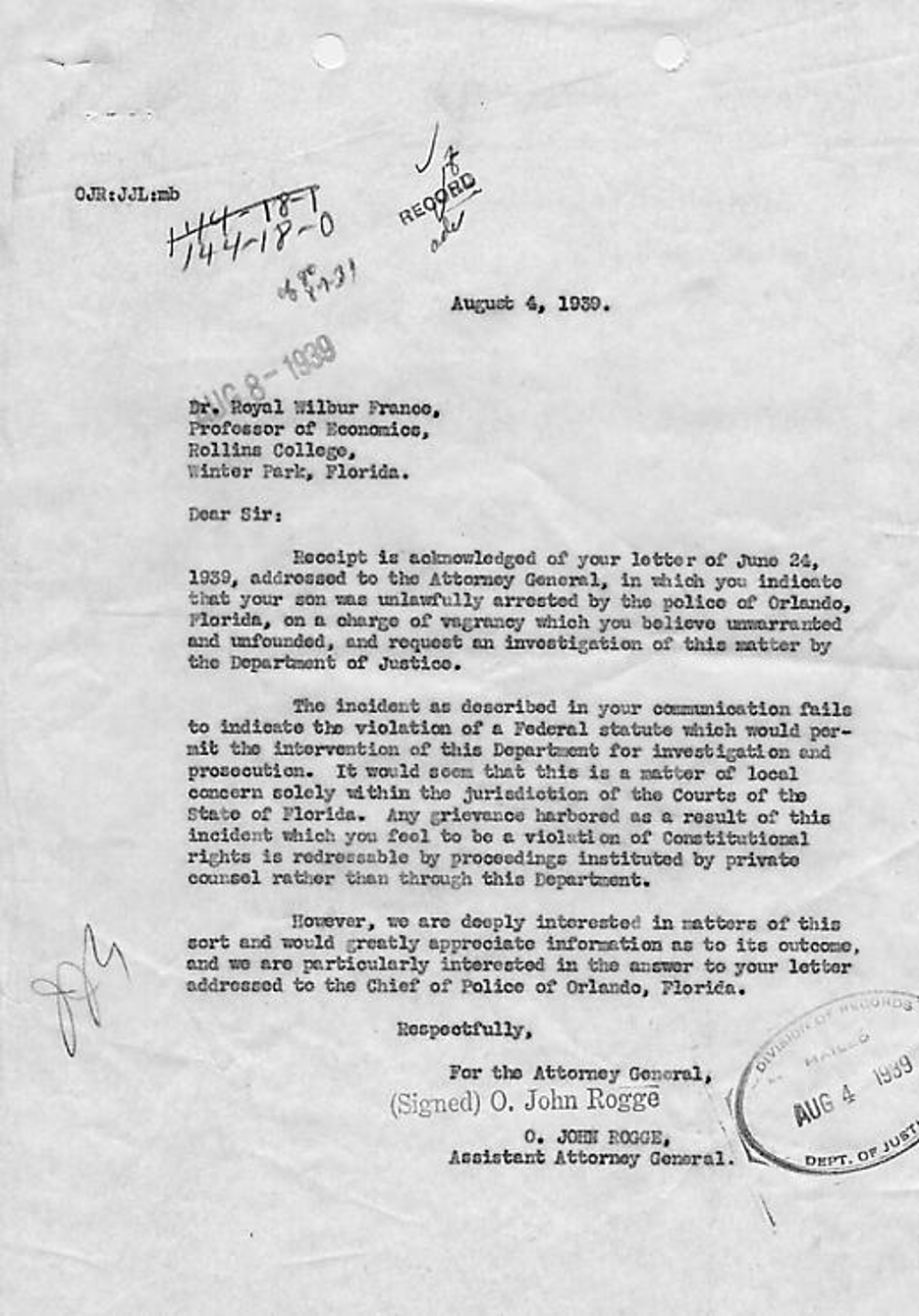

Although France had no way of knowing, his letter to the Attorney General was one of hundreds that had come pouring into the Civil Rights Unit (CRU) since its creation months earlier. Hundreds of people wrote claiming that their rights were being violated and asking the CRU to redress their grievances. Unfortunately—and paradoxically—AG Murphy had created a unit with a mission to protect a citizen’s civil rights but it operated without any authority to redress violations. The head of the section, John Rogge, admitted this in an article he wrote in 1939 where he stated that few statutes existed “making deprivation of civil liberties a Federal crime.” Without a federal laws or a federal court decision, the CRU was powerless to intervene in the states to protect those rights. This meant the CRU was also powerless to redress local police abuses of vagrancy laws. The officials of the CRU could do little except write letters empathizing with Individual grievances. Thus, France received a typical pro forma letter from the Assistant Attorney General:

Rollins College

Winter Park, Florida

Dear Sir,

Receipt of your letter of June 24, 1939, addressed to the Attorney General, in which you indicate your son was unlawfully arrested by the police of Orlando, Florida, on a charge of vagrancy which you believe unwarranted and unfounded, and request an investigation of this matter by the Department of Justice

The incident as described in your communication fails to indicate the violation of Federal statute which would permit the intervention of this Department for investigation and prosecution. It would seem that this is a matter of local concern solely within the jurisdiction of the Courts of the state of Florida. Any grievance harbored as a result of this incident which you feel to be a violation of Constitutional rights is redressable by proceedings instituted by private counsel rather than through this Department.

However, we are deeply interested in matters of this sort and would greatly appreciate information as to its outcome and we are particularly interested in the answer to your letter addressed to the Chief of Police of Orlando, Florida.

Respectfully,

I could find no record of France’s response to this letter (nor could I find any evidence that Chief Smith replied to France’s letter) but it must have been a terrible disappointment to learn of the Justice Department’s apparent helplessness in addressing local violations of civil rights.  The suggestion that civil rights violations were within the sole jurisdiction of local state courts and that France’s charges were “redressable” through the state court system was a non-starter and somewhat disingenuous, as Rogge must have known. Local governments, local police, local press and a majority of local white populations colluded to perpetuate the system that produced these violations. Only the federal judicial system could break this cycle. But Assistant AG Rogge was correct in claiming no federal statute, no federal court decisions and no national sentiment had formed to create conditions for the Justice Department to intervene to redress individual civil rights violations in the states. Not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 was the Justice Department provided with the authority to address some of these violations.

The suggestion that civil rights violations were within the sole jurisdiction of local state courts and that France’s charges were “redressable” through the state court system was a non-starter and somewhat disingenuous, as Rogge must have known. Local governments, local police, local press and a majority of local white populations colluded to perpetuate the system that produced these violations. Only the federal judicial system could break this cycle. But Assistant AG Rogge was correct in claiming no federal statute, no federal court decisions and no national sentiment had formed to create conditions for the Justice Department to intervene to redress individual civil rights violations in the states. Not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 was the Justice Department provided with the authority to address some of these violations.

African Americans had to wait even longer for remedies to vagrancy law violations in their neighborhoods. Four decades after France’s plea to the Attorney General, the Supreme Court accepted a case dealing with vagrancy laws. Had Royal France been alive he would not have been surprised to hear that the case originated in Florida. The basis for the case—Papachristou v City of Jacksonville (1972)—arose when police stopped two white women and two African American men who were driving on a main street in Jacksonville on their way to a nightclub. They were pulled over and arrested, the police reported, for violating Jacksonville’s vagrancy ordinance which prohibited “prowling in a car.” The officers claimed, without providing proof, that the defendants had stopped near a recently burgled used car lot. In a statement that contradicted decades of racial prejudice in historically segregated Jacksonville, the officers denied that racial mixture in the car affected their reason for arresting the four passengers.

![]() he Supreme Court decision, written by Justice William O. Douglas, declared the Jacksonville law unconstitutional on the grounds of the “vagueness doctrine.” Justice Douglas explained the doctrine in this way: “Those generally implicated by the imprecise terms of the ordinance…may be required to comport themselves according to the lifestyle deemed appropriate by the Jacksonville police and the courts. Where, [as in this case], there are no standards governing the exercise of the discretion granted by the ordinance, the scheme permits and encourages an arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement of the law. It furnishes a convenient tool for harsh and discriminatory enforcement by local prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed to merit their displeasure.” These laws resulted in a situation,” Douglas continued, in which “the poor and the unpopular are permitted to "stand on a public sidewalk... only at the whim of any police officer.” Douglas then rejected the claim by police departments that the enforcement of these ill-defined vagrancy laws made the streets safer. In words that Royal France would have applauded, Douglas declared that “the implicit presumption in these generalized vagrancy standards that crime is being nipped in the bud, is too extravagant to deserve extended treatment.”

he Supreme Court decision, written by Justice William O. Douglas, declared the Jacksonville law unconstitutional on the grounds of the “vagueness doctrine.” Justice Douglas explained the doctrine in this way: “Those generally implicated by the imprecise terms of the ordinance…may be required to comport themselves according to the lifestyle deemed appropriate by the Jacksonville police and the courts. Where, [as in this case], there are no standards governing the exercise of the discretion granted by the ordinance, the scheme permits and encourages an arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement of the law. It furnishes a convenient tool for harsh and discriminatory enforcement by local prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed to merit their displeasure.” These laws resulted in a situation,” Douglas continued, in which “the poor and the unpopular are permitted to "stand on a public sidewalk... only at the whim of any police officer.” Douglas then rejected the claim by police departments that the enforcement of these ill-defined vagrancy laws made the streets safer. In words that Royal France would have applauded, Douglas declared that “the implicit presumption in these generalized vagrancy standards that crime is being nipped in the bud, is too extravagant to deserve extended treatment.”

Douglas then concluded his brief with an unambiguous denouncement of the unequal administration of the vagrancy law of the “Jacksonville type.” Such vagrancy laws, he determined, “teach that the scales of justice are so tipped that even-handed administration of the law is not possible. The rule of law, evenly applied to minorities as well as majorities, to the poor as well as the rich, is the great [adhesive] that holds society together. The Jacksonville ordinance cannot be squared with our constitutional standards and is plainly unconstitutional.”

Along with other states, Florida was forced to rewrite its vagrancy law to conform to the Jacksonville decision. The new statute changed the terminology from vagrancy to “loitering” and redefined its meaning more precisely. The Orlando loitering ordinance, which operates under the state law, now reads: “It is unlawful for any person to “loiter and prowl” in a place, at a time, or in a manner not usual for law-abiding individuals, under circumstances that warrant a justifiable and reasonable alarm or immediate concern for the safety of persons or property in the vicinity.” Additionally, the law required a prosecutor must provide proof that “the individual loitered in a place, time and manner not usual for law-abiding citizens and that there was a justifiable alarm for safety in the vicinity.” As more than one state Appeals Court has noted, this law is still vague enough to allow for wide police discretion. “Loitering has long been an offense that occasionally tempts good police officers to exercise power in a manner that is inconsistent with the standards of our free society” one court declared. Still, the arbitrary arrests of African Americans for vagrancy that bedeviled neighborhoods such as Parramore for decades during the Jim Crow era has considerably diminished. Professor Royal France would surely have taken some satisfaction in knowing that in his small way he had advanced the cause of civil liberty for African Americans.

Wherein a larger question in a small place is suggested

![]() he arrest of Boyd France and its aftermath in the summer of 1939 can be viewed from an even larger historical perspective. The event provides an insight into the consequence of using vagrancy laws to justify police intrusion into “colored” neighborhoods, a practice that permeated all African American lives for multiple generations. No doubt some of the vagrancy arrests were justified. But the professed “law and order” basis for so many being taken into custody (the Sentinel reported a “flock of negroes arrested for vagrancy” on the same day the Boyd France incident) obscured a much more insidious purpose. Police intrusions into the Parramore neighborhood—as was the case in most African American neighborhoods throughout Florida—were meant to reinforce white supremacy, a collective white belief that justified and sustained racial segregation. Martin Anderson, in his June 13, 1939 editorial, perhaps unintentionally, provides a revealing window into white sentiment that led to granting broad police authority to enforce the vagrancy laws. Police officers, he noted in his editorial, were discharging their responsibility “to guide negroes to better citizenry,” and, the editor advised, “the rest of us [white citizens] should help our police do their job.” This excuse for the vagrancy arrests was not dissimilar to the Southern antebellum justification for slavery. In 1939, white people’s patronizing attitudes toward African Americans citizens had not changed much since Emancipation.

he arrest of Boyd France and its aftermath in the summer of 1939 can be viewed from an even larger historical perspective. The event provides an insight into the consequence of using vagrancy laws to justify police intrusion into “colored” neighborhoods, a practice that permeated all African American lives for multiple generations. No doubt some of the vagrancy arrests were justified. But the professed “law and order” basis for so many being taken into custody (the Sentinel reported a “flock of negroes arrested for vagrancy” on the same day the Boyd France incident) obscured a much more insidious purpose. Police intrusions into the Parramore neighborhood—as was the case in most African American neighborhoods throughout Florida—were meant to reinforce white supremacy, a collective white belief that justified and sustained racial segregation. Martin Anderson, in his June 13, 1939 editorial, perhaps unintentionally, provides a revealing window into white sentiment that led to granting broad police authority to enforce the vagrancy laws. Police officers, he noted in his editorial, were discharging their responsibility “to guide negroes to better citizenry,” and, the editor advised, “the rest of us [white citizens] should help our police do their job.” This excuse for the vagrancy arrests was not dissimilar to the Southern antebellum justification for slavery. In 1939, white people’s patronizing attitudes toward African Americans citizens had not changed much since Emancipation.

Finally, the way police enforced the vagrancy laws created a world in which African Americans invariably viewed the police as adversaries constantly threatening to disturb their daily lives. This unremitting condition explains why in no small measure these vagrancy laws left a permanent legacy of African American fear and distrust of law enforcement that remains unabated today.

3. Postscript

Dramatis Personae

Wherein the principals in this small drama are further identified

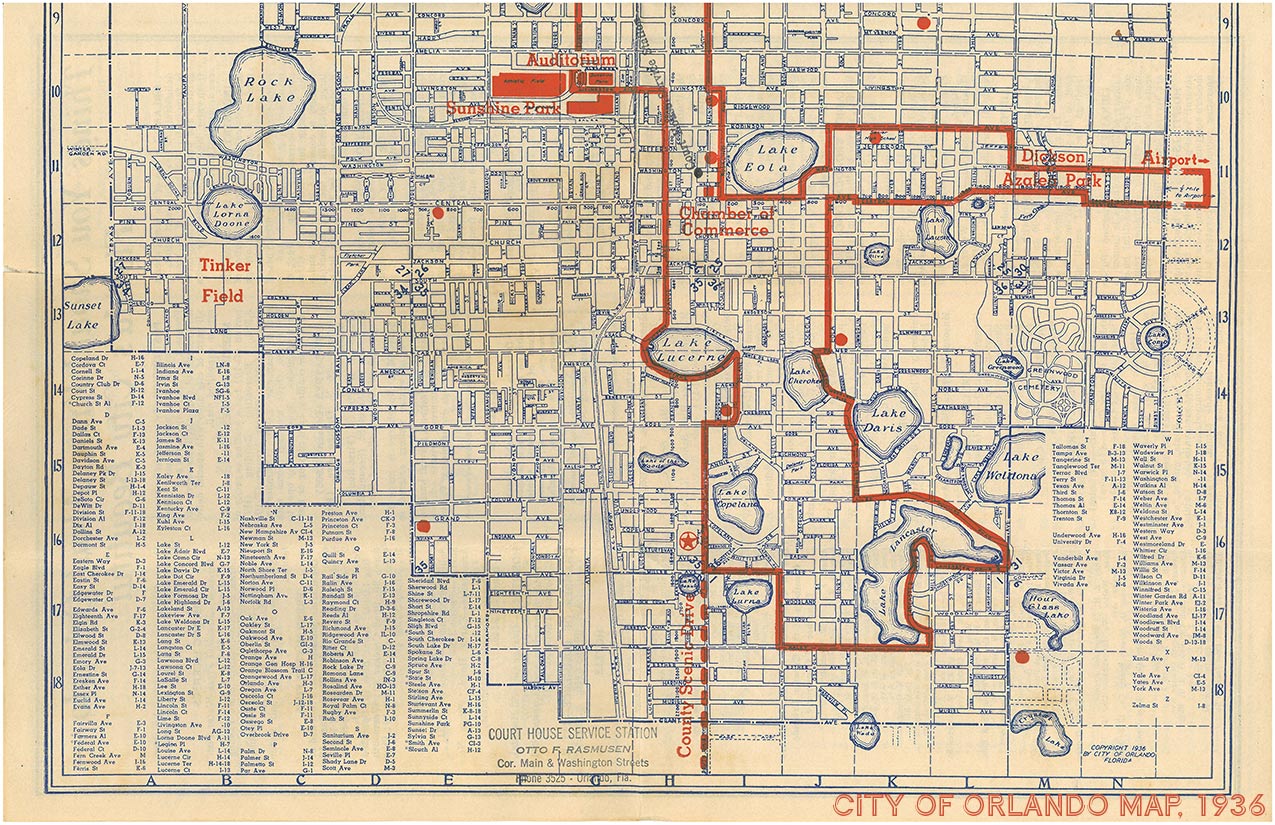

J. Roderick MacArthur

![]() he June 12, 1939 Orlando Sentinel article describing Boyd France’s arrest included this cryptic sentence: “With young France was an unnamed Rollins student who was not arrested.” That “young Rollins student” did have a name. It was J. Roderick (Rod) MacArthur, son of American businessman and philanthropist John D. MacArthur who established the renowned John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Rod was mostly responsible for the foundation’s so-called “Genius Grant.” Rod’s uncle was the noted playwright and screenwriter, Charles MacArthur, best known as co-author of the hit Broadway play The Front Page. He also wrote or co-wrote over 20 screen plays.

he June 12, 1939 Orlando Sentinel article describing Boyd France’s arrest included this cryptic sentence: “With young France was an unnamed Rollins student who was not arrested.” That “young Rollins student” did have a name. It was J. Roderick (Rod) MacArthur, son of American businessman and philanthropist John D. MacArthur who established the renowned John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Rod was mostly responsible for the foundation’s so-called “Genius Grant.” Rod’s uncle was the noted playwright and screenwriter, Charles MacArthur, best known as co-author of the hit Broadway play The Front Page. He also wrote or co-wrote over 20 screen plays.

Rod MacArthur entered Rollins College as a freshman in 1938 but left before graduation. Later he served as an ambulance driver in the American Field Service operating in France. He stayed on in France after the war and in 1947 married Christiane L’Entendart, a French citizen. (One of the couple’s children, John R. (Rick) Macarthur, is now publisher and president of Harper’s Magazine).

Rod returned to the United States to work in his father’s insurance business but left after a short time to start his own company, Bradford Exchange, which sold collectible plates. The financial success of the company allowed Rod to create the J. Roderick Macarthur Foundation and the J. Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center dedicate to supporting the causes of civil liberties. It is not inconceivable that the gratuitous arrest of his best friend in 1939, while he remained silent, had some influence on Rod’s later passionate commitment to championing civil liberties. Before he died in 1984, the American Civil Liberties Union bestowed upon him the Roger Baldwin Award for exemplary service in the cause of human rights worldwide.

Harold Boyd France

![]() oyd France graduated with honors from Rollins in 1941 and joined his lifetime friend, Rod, in the American Field Service serving in France. He remained in Paris after the war as a reporter for the Reuter wire service. He and his wife Denise were honeymooning in the French Mediterranean town of Port-de-Bouc in July 1947 when 4,500 beleaguered Jewish refugees of the famed Exodus 1947 arrived. The British had denied them entry into the Palestine, forced them on three deportation ships and sent to Port-de-Bouc. By this time the plight of the refugees had become an international sensation. When they refused to disembark at Port-de-Bouc, Boyd France swam out to a small boat tethered close enough to one of the ships for him to interview the passengers and the captain. His account in Reuters gained world-wide attention. Later he was appointed the Paris bureau chief for Business Week in 1948 and later joined the Washington bureau in 1951. He served as chief White House and State Department correspondent until retiring in 1986. He died in March 2009.

oyd France graduated with honors from Rollins in 1941 and joined his lifetime friend, Rod, in the American Field Service serving in France. He remained in Paris after the war as a reporter for the Reuter wire service. He and his wife Denise were honeymooning in the French Mediterranean town of Port-de-Bouc in July 1947 when 4,500 beleaguered Jewish refugees of the famed Exodus 1947 arrived. The British had denied them entry into the Palestine, forced them on three deportation ships and sent to Port-de-Bouc. By this time the plight of the refugees had become an international sensation. When they refused to disembark at Port-de-Bouc, Boyd France swam out to a small boat tethered close enough to one of the ships for him to interview the passengers and the captain. His account in Reuters gained world-wide attention. Later he was appointed the Paris bureau chief for Business Week in 1948 and later joined the Washington bureau in 1951. He served as chief White House and State Department correspondent until retiring in 1986. He died in March 2009.

Royal Wilbur France

![]() n 1952, at an age when most faculty were considering retirement, Professor Royal France decided to undertake another journey. His years at Rollins College had been one of professional satisfaction and personal contentment but now he was restive: “I felt increasingly that I was too much at ease in Zion,” he reflected, “while one of history’s great struggles for the preservation of free speech was taking place right here in our own country.” The “great struggle” he referred to was the effort to assist those threatened by the anti-communist crusade conducted by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. France had experienced personally the First Red Scare when, in 1920, he opposed the expulsion of duly elected socialists from the New York Legislature. He was now witnessing how that kind of hysteria was turning even more virulent in the emerging Cold War. “The witch hunters” he noted with dismay, “were riding high in Congress and a pall of fear had effectively silenced questioning and dissent. People were being hounded in a shameless fashion for opinions they held, or which they may have held. Those who attempted to speak out against out against the evil were being pilloried. More and more people, seeing what happened to those few, withdrew.”

n 1952, at an age when most faculty were considering retirement, Professor Royal France decided to undertake another journey. His years at Rollins College had been one of professional satisfaction and personal contentment but now he was restive: “I felt increasingly that I was too much at ease in Zion,” he reflected, “while one of history’s great struggles for the preservation of free speech was taking place right here in our own country.” The “great struggle” he referred to was the effort to assist those threatened by the anti-communist crusade conducted by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. France had experienced personally the First Red Scare when, in 1920, he opposed the expulsion of duly elected socialists from the New York Legislature. He was now witnessing how that kind of hysteria was turning even more virulent in the emerging Cold War. “The witch hunters” he noted with dismay, “were riding high in Congress and a pall of fear had effectively silenced questioning and dissent. People were being hounded in a shameless fashion for opinions they held, or which they may have held. Those who attempted to speak out against out against the evil were being pilloried. More and more people, seeing what happened to those few, withdrew.”

He and his wife moved to Washington where he joined a group of civil rights lawyers because, he said “I could not be at peace with myself until I had genuinely and without reserve offered myself, at this crucial moment in history, to defend the principles which lay at the basis of my philosophy of life.” His first case was in Baltimore where he defended six Communists who had been charged with violating the Smith Act. Faced with three “hard-faced” justices, France lost the case and the defendants went to jail. For the next several years, he worked with the ACLU and other civil rights groups involved in cases ranging from an unsuccessful appeal of the death sentence of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the defense of a group of clergymen accused of Communist subversion. In France’s words, he was in “a whirlpool of court actions, appearances before Congressional committees, working with the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Religious Freedom Committee.” He was serving as director of the National Lawyers Guild, a progressive civil rights organization, when he died in July 1962.

Martin Andersen

![]() artin Andersen was publisher of the Orlando Sentinel from 1931 to 1965. By 1939 he had earned a reputation as one of the most influential people in Central Florida and to some extent throughout the state. As described by one of his reporters, he was “tough, savvy, blunt, down-to-earth, controversial, at times strident and hot-tempered and at times generous and compassionate. He was one of the last two-fisted publishers of the old roughhouse school of one-man newspapering.” A native of Mississippi, he arrived in Orlando steeped in the traditional white southern attitude toward race relations. He was outspoken in his contempt for civil rights advocates such as Royal France. As evident in the 1939 editorial, he used his editorial platform to reinforce the prevailing Jim Crow segregation system. While he was publisher/editor few public figures could get elected in Central Florida without the endorsement of the Sentinel. After World War II, Anderson became a leading advocate of development in Central Florida. He was a driving force behind the area’s road network, including Interstate 4, the building of what would become an international airport and was at the forefront of bringing Disney World to Orlando. In 1958, Florida Trend Magazine chose Andersen as one of Florida’s most influential men.

artin Andersen was publisher of the Orlando Sentinel from 1931 to 1965. By 1939 he had earned a reputation as one of the most influential people in Central Florida and to some extent throughout the state. As described by one of his reporters, he was “tough, savvy, blunt, down-to-earth, controversial, at times strident and hot-tempered and at times generous and compassionate. He was one of the last two-fisted publishers of the old roughhouse school of one-man newspapering.” A native of Mississippi, he arrived in Orlando steeped in the traditional white southern attitude toward race relations. He was outspoken in his contempt for civil rights advocates such as Royal France. As evident in the 1939 editorial, he used his editorial platform to reinforce the prevailing Jim Crow segregation system. While he was publisher/editor few public figures could get elected in Central Florida without the endorsement of the Sentinel. After World War II, Anderson became a leading advocate of development in Central Florida. He was a driving force behind the area’s road network, including Interstate 4, the building of what would become an international airport and was at the forefront of bringing Disney World to Orlando. In 1958, Florida Trend Magazine chose Andersen as one of Florida’s most influential men.

Andersen crossed swords with France again a few years after the 1939 verbal encounter. In June 1945, shortly after the surrender of Germany, France delivered a baccalaureate address in the college chapel on the nature of the Allied peace terms with Germany, where he argued that Nazi leaders should be held accountable but the majority of the Germans, who were “good people,” should not be punished.” That kind of vengefulness, he told the Rollins seniors, had contributed to the rise of Hitler after World War I. Anderson published his speech in the Sentinel and then followed it with a stinging editorial accusing France of being guilelessly pro-German. “We think that Dr. France,” Andersen intoned, “who thinks the German people is a great people should retire from his rather questionable glories at Rollins and join these ‘great people’ in what he would call a happy future.” Three years later, France could have gloated to Anderson that his argument for separating the behavior of the German people from Nazi leaders was precisely the basis for the 1948 Marshall Plan. He didn’t. Unlike many of his critics, malice was not in France’s nature.

William Henry "Billy" Smith (Chief of Police)

![]() here is little recorded evidence of Billy Smith’s background. His brief obituary in the Orlando Evening Star (June 6, 1955) has him as a native of Illinois but other accounts depict his growing up in Mississippi. Apparently he moved to Orlando in 1895 and for years worked as a house painter. From 1913 to 1916 he served as “town marshall,” an amorphous position that apparently was a precursor to chief of police. After 1916, Smith moved between the sheriff’s office and the police department until finally in 1934 he was appointed Orlando’s police chief, a position he held until 1940. He died in 1955. The brevity of the obituary of a 20 year veteran of the police department, 7 as it chief, may speak volumes about the reputation of Billy Smith. In one area at least—forcefully enforcing the segregation system—Smith had the approving support of Orlando’s white community.

here is little recorded evidence of Billy Smith’s background. His brief obituary in the Orlando Evening Star (June 6, 1955) has him as a native of Illinois but other accounts depict his growing up in Mississippi. Apparently he moved to Orlando in 1895 and for years worked as a house painter. From 1913 to 1916 he served as “town marshall,” an amorphous position that apparently was a precursor to chief of police. After 1916, Smith moved between the sheriff’s office and the police department until finally in 1934 he was appointed Orlando’s police chief, a position he held until 1940. He died in 1955. The brevity of the obituary of a 20 year veteran of the police department, 7 as it chief, may speak volumes about the reputation of Billy Smith. In one area at least—forcefully enforcing the segregation system—Smith had the approving support of Orlando’s white community.

~What were the Black Codes and what does the author mean when he states that the Black Codes “morphed into the Jim Crow segregations system”?

~Did the two white students violate Orlando’s vagrancy law or did they simply “go against a common understanding”?

~Was Officer Phelps acting correctly when he arrested Boyd France?

~Was Boyd France courageous or unwise to get into an argument with Office Phelps? Should his friend have joined Boyd in confronting Officer Phelps? Since he did not was he less courageous? What would you have done in that situation?

~What does the phrase “white consensus around segregation” mean? What is the evidence for this? In addition to the vagrancy laws, what other ways were African Americans affected by the segregation system?

~What are the implications of editor Martin Anderson’s statement that Orlando police officers were expected “to guide negroes to better citizenship.’? Would that apply to white citizens aa well?

~Discuss both sides of the confrontation between Professor France and Chief of Police Billy Smith.

~Professor France thought local vagrancy laws violated the Bill of Rights. Which one? And do you think he was correct.

~Professor France thought the Justice Department should intervene in to protect against local and state violations of the Bill of Rights.. Do you agree? Why or Why not.

~Summarize Justice Douglas’s argument in the Jacksonville case dealing with state and local vagrancy laws. Why did he rule that the prevailing vagrancy laws were unconstitutional.

~What is the difference between the 1939 and the present Florida vagrancy law.

~Research Topic: Think of a local incident that reveals a larger issue and write an essay using the concept of microhistory

Notes have been presented inline through superscripted numbers in the article itself. Should you want to read the notes on their own, click to expand.

eFHQ is a collaboration between the Florida Historical Society and the Florida Historical Quarterly, as well as the Department of History and the Center for Humanities and Digital Research at the University of Central Florida.