![]() n 1900, African American William Gibson lived on a small farm, rented by his uncle, in Holmes, Mississippi, with his mother, extended family members and siblings. When Gibson married his wife Icy, he left his childhood home and moved sixty miles to a farm he rented in Sunflower, Mississippi. The Gibsons lived in Sunflower until they moved to Hannibal Square, the African American neighborhood of Winter Park, a small, wealthy town in central Florida. By 1930 Gibson had four children, owned a home valued around $1,800, and was no longer a farm hand but a laborer for a local golf course. This upward mobility was unusual for farmers in the American South during the 1920s, especially for African Americans.

n 1900, African American William Gibson lived on a small farm, rented by his uncle, in Holmes, Mississippi, with his mother, extended family members and siblings. When Gibson married his wife Icy, he left his childhood home and moved sixty miles to a farm he rented in Sunflower, Mississippi. The Gibsons lived in Sunflower until they moved to Hannibal Square, the African American neighborhood of Winter Park, a small, wealthy town in central Florida. By 1930 Gibson had four children, owned a home valued around $1,800, and was no longer a farm hand but a laborer for a local golf course. This upward mobility was unusual for farmers in the American South during the 1920s, especially for African Americans.

Gibson’s journey from Mississippi to Hannibal Square reflected both the dramatic changes that African Americans faced in the interwar years and the unusual employment opportunities offered in Winter Park. Winter Park was founded in the late 1800s as a seasonal home for wealthy northerners, who spent their winters in the relative balm of Central Florida. In its early years, Winter Park augmented this prosperous tourism with more traditional southern economies such as agriculture, specifically turpentine and citrus production. In 1881, the Sanford/Orlando railroad line made transportation south easier, linking the St. John’s River directly into Central Florida, which boosted winter visitation and connected the area to larger regional and national markets.

Gibson’s journey from Mississippi to Hannibal Square reflected both the dramatic changes that African Americans faced in the interwar years and the unusual employment opportunities offered in Winter Park. Winter Park was founded in the late 1800s as a seasonal home for wealthy northerners, who spent their winters in the relative balm of Central Florida. In its early years, Winter Park augmented this prosperous tourism with more traditional southern economies such as agriculture, specifically turpentine and citrus production. In 1881, the Sanford/Orlando railroad line made transportation south easier, linking the St. John’s River directly into Central Florida, which boosted winter visitation and connected the area to larger regional and national markets. Bountiful available land, numerous lakes, mild weather, and ocean access drew northerners south and encouraged the construction of winter homes, hotels, and recreational facilities such as golf courses. Thus, as the city of Winter Park grew, its economy became increasingly atypical of many other southern towns. The founders of Winter Park designed adjacent Hannibal Square to house the town’s Black domestic help. The focus on tourism and domestic work in Hannibal Square created a different lived experience for its African American inhabitants, reflective of trends in other Florida tourist towns.

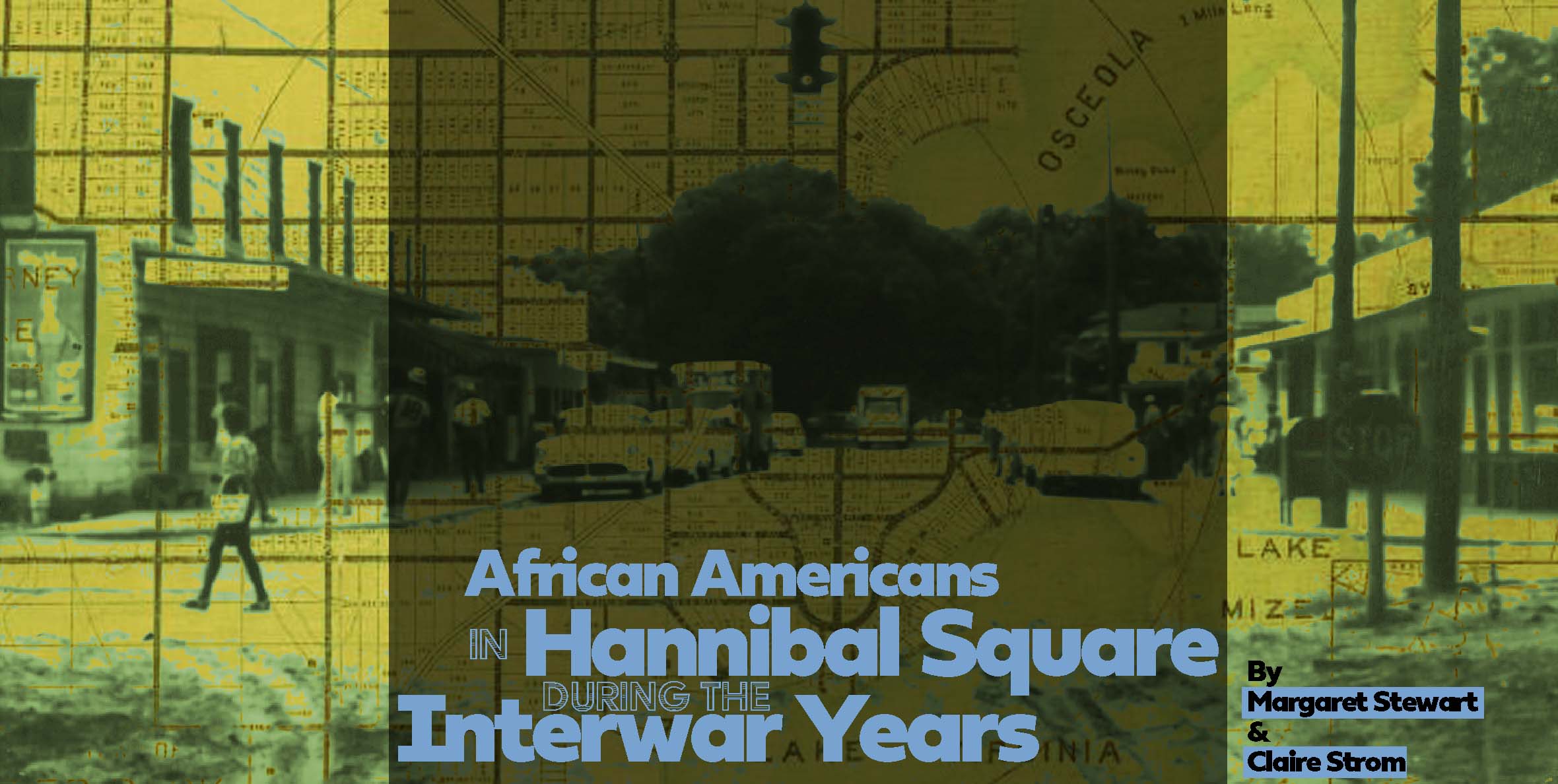

African American residents in Hannibal Square increased as the economy grew in the interwar years: from 506 in 1920, to 1,047 in 1930, to 1,335 in 1940 (see figure 1). Maps of Hannibal Square reveal this massive expansion: lots that were vacant in 1930 became homes to large families by 1940. From the 1920s to the 1940s, Hannibal Square also experienced the growth of a black middle class and prolonged black businesses that developed, in part, because of the surrounding wealthy area.

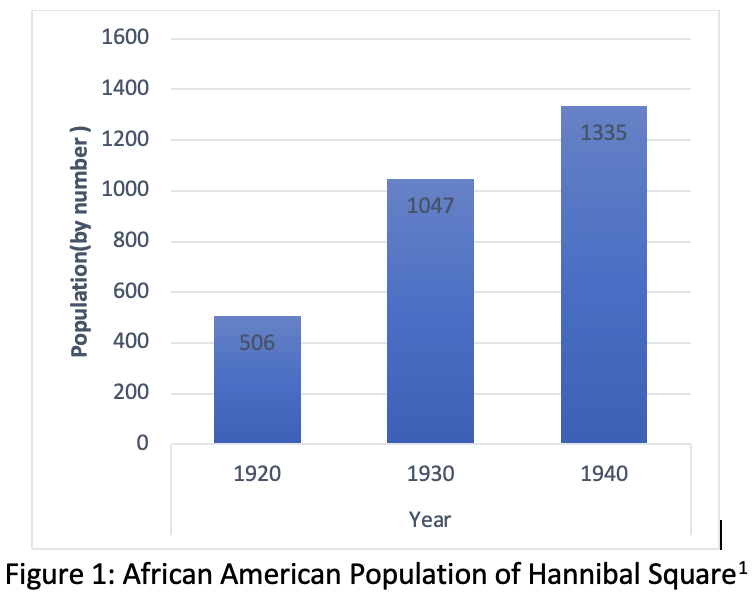

The influx of African Americans to Hannibal Square was partly due to larger national trends, most notably the Great Migration, the massive exodus of African Americans escaping from the poor rural agricultural South during the 1920s and 1930s. While the historiography of the Great Migration focuses on the movement of Blacks to northern cities, especially New York and Chicago, a significant population shift also occurred within the South. Many of the African Americans arriving in Hannibal Square in the 1920s came from rural agricultural regions of southeastern United States. Of the 30 percent of African American households that were in Hannibal Square in 1930 that can be found in previous federal censuses (see figure 2), 51 percent came from other regions of Florida, 37 percent came from Georgia, and 6 percent came from South Carolina. The remaining 6 percent came from a mixture of areas around the United States, including North Carolina, Tennessee, New Jersey, and Delaware.

The 1920s migration within Florida came mainly from small, rural agricultural towns characterized by areas with deteriorating industries. A number of Blacks in north Florida and the Panhandle counties headed south to central Florida in search of economic opportunity. Gadsden and Jefferson counties accounted for a large portion of the migrants to Hannibal Square from north Florida. Gadsen boasted a large shade tobacco industry in the early to mid-1900s, which spurred much of its economy, in both the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. Jefferson County, in contrast, thrived as through food production. African Americans worked on small family vegetable farms. Agricultural industries boomed during World War I, with products in high demand: in 1918 an article from the Tallahassee Democrat boasts a headline that “Gadsen expects 3,500,000 from tobacco crops” for the fiscal year.

The end of the war saw an immediate contraction of demand, which combined with a decline in US agricultural sales abroad, to send crop prices plummeting. Farmers across the country suffered, and marginal farmers, including African Americans, often found themselves unable to continue farming. In northern Florida, specifically, many African American farmers lost their farms to consolidation as richer white farmers leveraged low prices to buy out poorer ones. By the middle of the decade, many farmers were selling up and getting out while they still could, with an advertisement in the Tampa Bay Times offering 680 acres of land in Gadsen County “well adapted to the raising of cigarette tobacco” at “the very lower price of $27.50 per acre.”

James Simmons was one of these displaced farmers from northern Florida who moved to Hannibal Square. In 1920, Simmons was a farm laborer who, together with his wife Rosebud, rented a home in Quincy, the county seat of Gadsen. By 1930, he had moved to Hannibal Square and rented a home on Lyman Avenue, which housed Simmons, his wife, Ula, and their four children, his sister-in-law and niece, and a boarder. Simmons worked as a laborer in Winter Park. Throughout the rest of the decade, Simmons worked as a gardener before returning to farming in the 1940s.

Migration from other parts of the South also reflected this trend. Those coming from Georgia or the Carolinas often came from poor agricultural areas in decline. For example, Lesso Fennell migrated to Winter Park with his wife by 1930 to work as a laborer in Hannibal Square. Fennell’s family history is one of successive migrations. The family was from North Carolina, but Fennell was born in Georgia and first appeared in the census in 1910 at age seven, living in Waresboro, Georgia. Fennell’s father worked in the turpentine industry, while his older brother, Robert, worked the farm the family rented. By 1920, the family had returned to North Carolina, to Long Creek, a small township outside Charlotte. Now the oldest child at home, Fennell worked with his father on the land the family rented. This area of North Carolina focused mainly on production of tobacco, with some manufacturing of textiles—a predominantly white industry. By 1930, Fennell—likely a victim of the contraction of the tobacco market--was a grove worker in Winter Park.

African Americans who migrated from the North during the 1920s to Winter Park were similarly propelled by economics. Unlike Blacks that were coming from the South, mainly migrating from small towns with a population of 5,000 or less, those migrating from the North came from larger urban centers. Nelson Horton had been born in Georgia in the mid-1800s. By the turn of the century, he lived with his brother in Winter Park. He moved out of his brother’s house before 1910, and, by 1920 was living in Wilmington, Delaware. In Wilmington, Horton worked in house construction and shared a rental with two other African American men--one who worked in the shipyards and one who worked in a leather factory. The fourth person in the house, Myrtle Armstrong, worked in a laundry. Horton may have moved north to benefit from the economic boom surrounding World War I. Wilmington, situated on the Delaware River, experienced significant urbanization during this time, with steel factories, chemical manufacturing, and shipyards sprouted up to support the war effort. The good times did not last for long, however. By the early 1920s, Horton was back in Winter Park, not living with his brother, but with his wife, Faith, in a house they owned on Carolina Avenue. He lived there until his death in 1942. Horton’s short sojourn north seems to be motivated by economic factors and a desire to profit from the war.

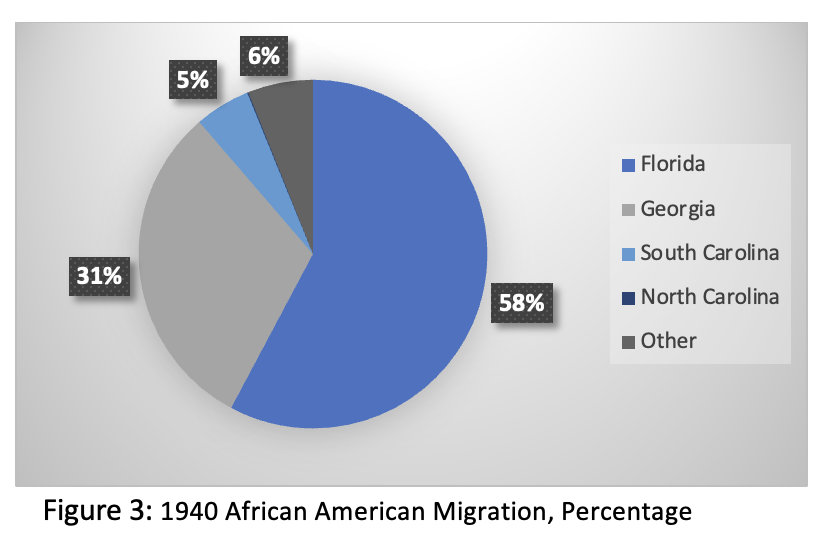

During the 1930s migration to Hannibal Square continued but slowed. The African American population grew from 1,047, to 1,335 (27.5 percent), a must less significant increase than the previous decade. Based on data from approximately 35 percent of the African American families in Winter Park identifiable in the 1940 census, migration to Winter Park from other places in Florida grew by 7 percent to 58 percent, and migration from Georgia reduced slightly from 38 to 32 percent (see figure 3). Additionally, movement from cities within fifty miles of Winter Park, such as Sanford, Orlando, Haines City, and Oviedo, became increasingly common in the 1930s. For example, Linnie Allen was a widowed dressmaker who lived in Orlando in 1930 with her child and two other roomers. During the 1930s, she moved to Winter Park and started working as a laundry worker. At the time, Winter Park had many laundry services to cater to its wealthy white residents. The most prominent, American Laundry Service and White Star on Orlando Avenue advertised many services boasting “now, more than ever before, you may obtain the best in dry cleaning…get your clothes done a ‘little better.’” The growth of the African American community in Winter Park during the decade was less than the state average for urban areas, which was 36.5 percent, and for Orlando at 37.9 percent. However, statewide, the number of African Americans grew only 19 percent from 1930 to 1940, indicating that Winter Park was still an attractive destination to many.

Not all the new Black residents in Hannibal Square in the interwar years came as the result of migration. Several families who had moved to the Hannibal Square in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, established deep roots in the community. Their large multi-generational families contributed to the population’s growth. An example of one of these large African American families were the Lemons. Elisha Lemon was resident in Winter Park in 1900, where he rented a home with his wife, Maggie, his children, and his widowed mother. By 1910, the family was living on a farm they owned free and clear on Forbes Avenue. Elisha was employed as a woodchopper, his eldest child, Henrietta, was a nineteen-year-old laundry worker, seventeen-year-old son, William, was a day laborer, and the second son, Elisha, was a fifteen-year-old worker in a citrus packing house. Ten years later, the family was still on the farm. William and Elisha had left home, and Henrietta had returned home having been married and widowed during the decade and was working as a cook. Another daughter, Melinda, was single at twenty-four and worked as a laundry worker, while the oldest son at home was eighteen-year-old Stephen who was employed in the groves. Elisha lived in Winter Park until his death in 1929. He left his wife and children, Henrietta, Henry, John, Elisha, Melinda, John, Stephen, Alexander, Theresa, Gracie, and Walter. His children, and grandchildren, continued to live in Hannibal Square. The year after Elisha’s death, Maggie had moved to 105 Pennsylvania Avenue in 1930, and was living with all eleven of her children, plus her son, Elisha’s, wife Nannie and their five children including two sets of twins! During the Great Depression, perhaps with the continued contraction of the agricultural sector, Elisha became a plasterer. Elisha died in 1962, and his wife, Nannie petitioned successfully to have a military headstone placed for him at Pinewood Cemetery because of his service in World War I.

The Ambroses were another large extended family. Charles Ambrose moved to Winter Park in the late 1800s with his wife, Missouri, from Madison, Florida. Together they had ten children. Their children continued to live in Winter Park, while moving houses and changing occupations. One of their sons, Arthur, married twice, and worked many jobs, including laborer, porter, and chauffeur. Their eldest son, Chester, had moved back in with them by 1930 after a divorce, bringing two granddaughters. By 1940, Chester was still living at home, and their youngest son, Charles Ambrose Jr., also lived with his parents and worked as a yardman. Chester had registered for the draft for World War I and Charlie registered for it for World War II, a reflection of the large size of the family.

The principal reason for migration to Hannibal Square appeared to be the relatively good employment opportunities available in comparison to much of the rest of the country. The migration from other urban centers to Hannibal Square seemed to follow the rising unemployment associated with the Great Depression. The economies of many of Florida’s larger cities relied heavily on tourism, and, although tourism declined during the early days of the depression, “a comeback was evident by 1934” and the state experienced its largest tourist season to date in 1935.

The effects of the depression were reflected in migration figures: the white urban population rose only slightly the while the African American population living in urban areas in Florida decreased from 27.7 percent in 1930 to 27.4 percent. Life outside of large cities was more attractive because of the cheaper living expenses and possibility of being more self-sustaining. Hannibal Square’s economy survived through the Depression, perhaps due to the significant wealth present in the white community. These affluent permanent and seasonal residents continued to create employment opportunities that attracted African Americans to the area. Therefore, between 1920 and 1940, although national and state migration and employment trends for African Americans in relation to agriculture and manufacturing were reflected in Hannibal Square, the wealthy Winter Park community created an environment where domestic labor was much more significant than found elsewhere in the nation or state.

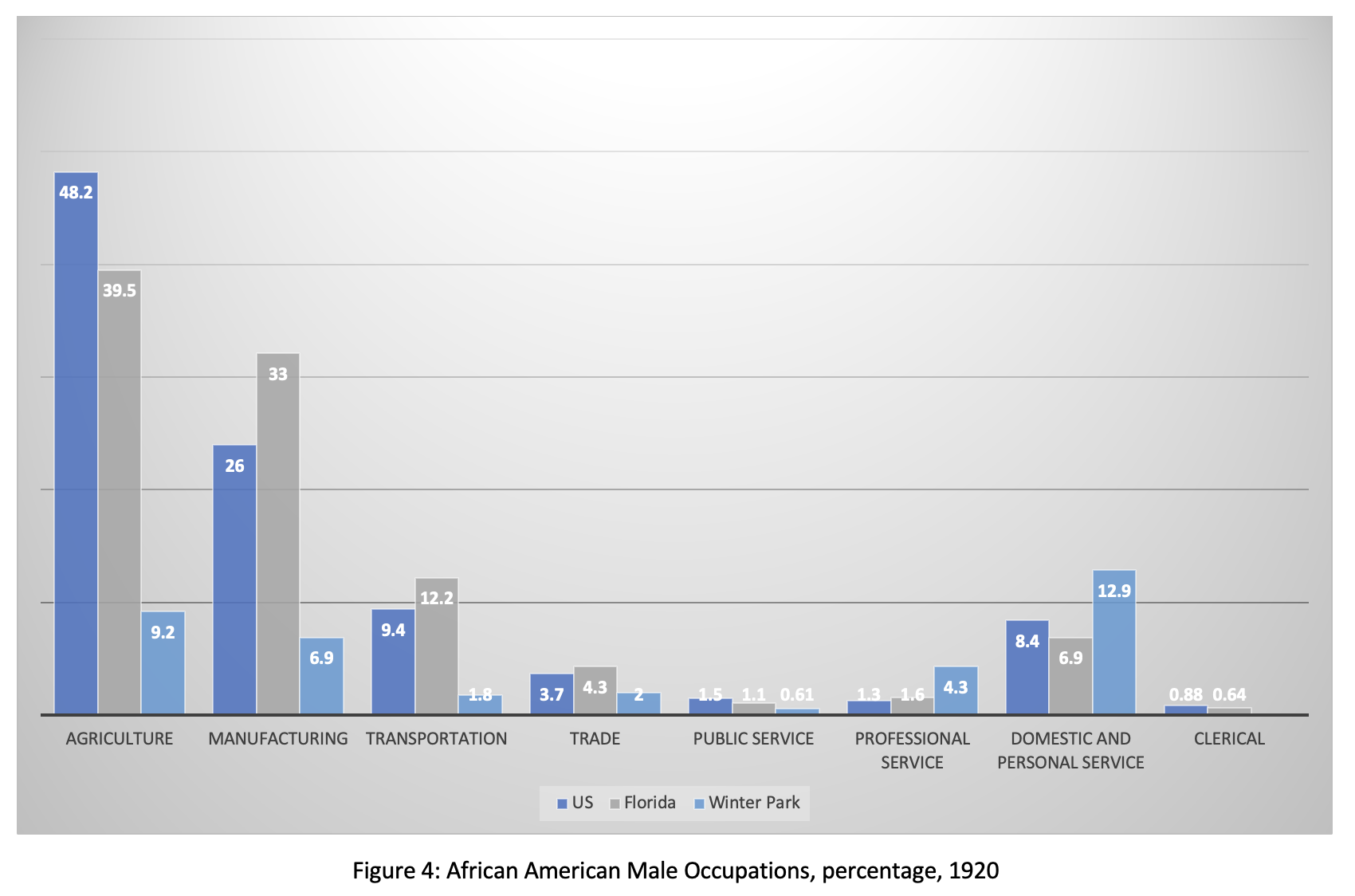

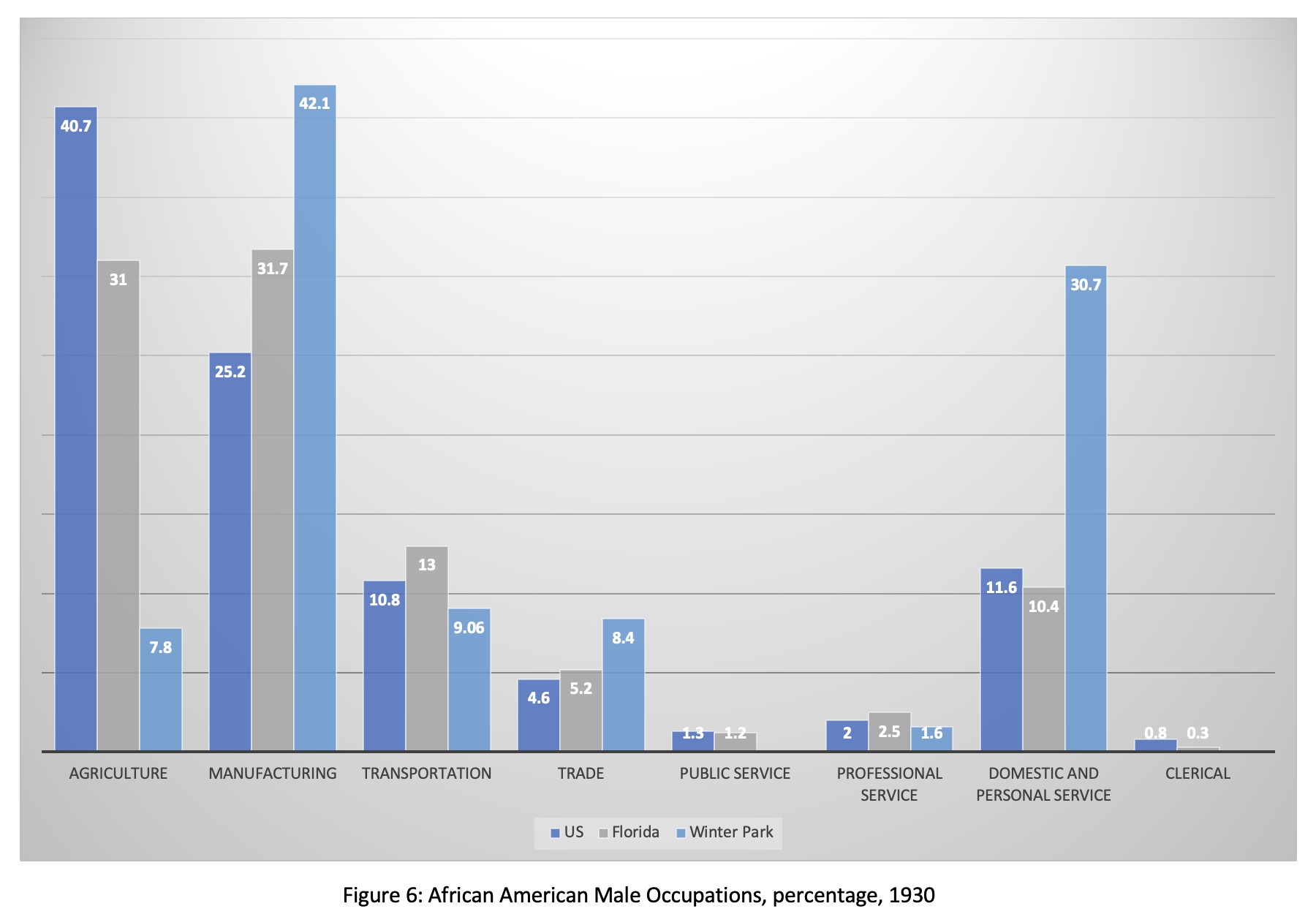

In general, the occupations of African Americans in Winter Park differed from most other agriculturally based small towns in the rest of the state and the nation, reflecting the nature of the town as an elite white resort. In 1920 (see figure 4), 49 percent of African American men in the United States more broadly worked in agriculture.  In the South, they worked on the three most lucrative cash crops: cotton, rice, and tobacco. Their labor was most commonly found on large plantations under a system known as sharecropping. By the second decade of the twentieth century, sharecropping, which had been met by many African Americans with hope at the end of the Civil War, had degenerated into a crop peonage trap that bound African Americans and poor whites in a cycle of debt and poverty. This was exacerbated in the 1920s, when, after an increase in crop prices during World War I, agricultural prices plummeted, forcing the sector into depression. In the South, this agricultural crisis was heightened by a widespread infestation of cotton crops by the boll weevil, and, in 1927, by the devastating flood of the Mississippi River that destroyed crop land and impoverished rural communities along the river. While white landowners generally survived such environmental trials, it was often at the expense of their sharecroppers, who found themselves pushed off the land. Many of these joined the black rural exodus to the North that had begun during the Great War; the Great Migration to industrial jobs throughout the Rust Belt. By 1930 (see figure 6), the number of Black men who worked in agriculture across the country had dropped to 42 percent, while the number employed in manufacturing rose from 25 to 26 percent, reflecting the increase of jobs in urban centers. This is evident in the multiple farms that began to go on sale throughout the rural South. On August 5, 1925, a Georgian newspaper, the Atlanta Constitution published an article titled “Premier List of Georgia Farms: More than two hundred desirable farms…eighty thousand acres” of land. This decade also saw an increase in the small number of black men who worked in domestic service, from 9 to 12 percent.

In the South, they worked on the three most lucrative cash crops: cotton, rice, and tobacco. Their labor was most commonly found on large plantations under a system known as sharecropping. By the second decade of the twentieth century, sharecropping, which had been met by many African Americans with hope at the end of the Civil War, had degenerated into a crop peonage trap that bound African Americans and poor whites in a cycle of debt and poverty. This was exacerbated in the 1920s, when, after an increase in crop prices during World War I, agricultural prices plummeted, forcing the sector into depression. In the South, this agricultural crisis was heightened by a widespread infestation of cotton crops by the boll weevil, and, in 1927, by the devastating flood of the Mississippi River that destroyed crop land and impoverished rural communities along the river. While white landowners generally survived such environmental trials, it was often at the expense of their sharecroppers, who found themselves pushed off the land. Many of these joined the black rural exodus to the North that had begun during the Great War; the Great Migration to industrial jobs throughout the Rust Belt. By 1930 (see figure 6), the number of Black men who worked in agriculture across the country had dropped to 42 percent, while the number employed in manufacturing rose from 25 to 26 percent, reflecting the increase of jobs in urban centers. This is evident in the multiple farms that began to go on sale throughout the rural South. On August 5, 1925, a Georgian newspaper, the Atlanta Constitution published an article titled “Premier List of Georgia Farms: More than two hundred desirable farms…eighty thousand acres” of land. This decade also saw an increase in the small number of black men who worked in domestic service, from 9 to 12 percent.

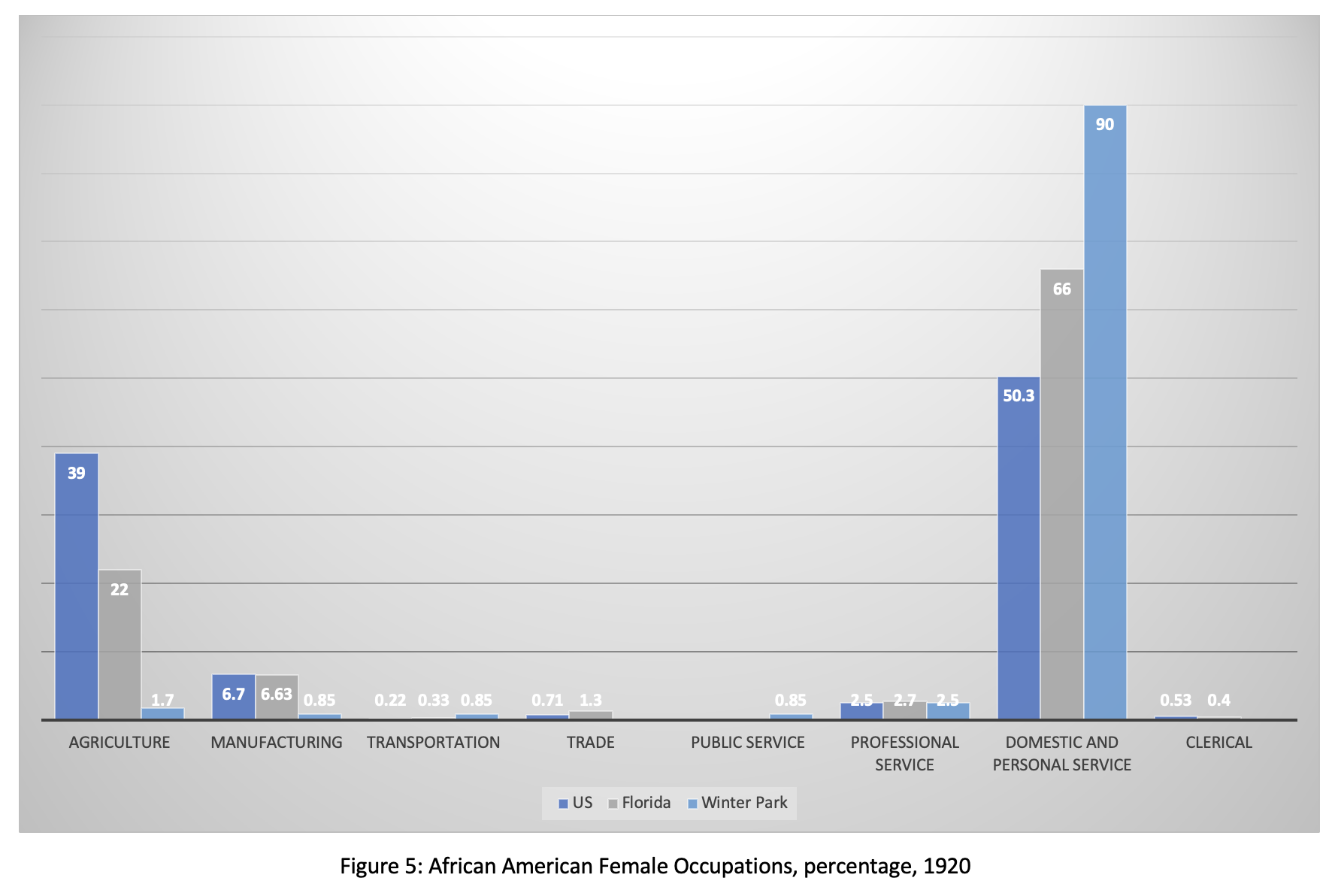

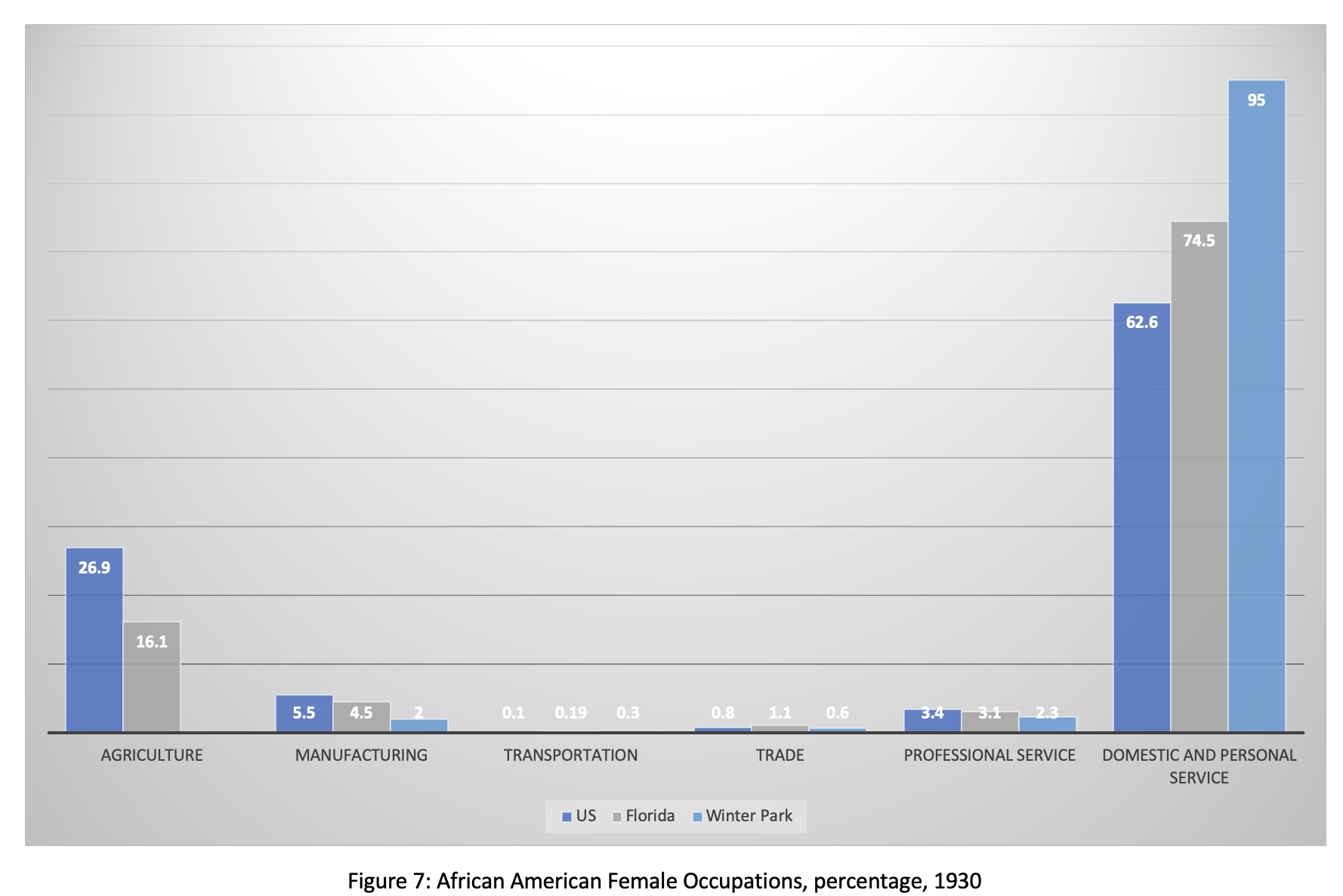

African American men were rarely employed in domestic service; this was where most African American women found employment. In 1920 (see figures 5 and 7), 50 percent of employed African American women in the United States worked within domestic service and this increased to 63 percent by 1930. Most women were employed as laundry workers, maids, cooks, and nannies by wealthy families. Generally, middle-class white society viewed it as more acceptable and safer to hire Black women in homes than Black men due to the perception and stereotypes that surrounded African Americans. Fearmongers, from politicians to newspaper editors, had portrayed Black men as lascivious beasts for generations, while Black women were often cast as a “mammy:” a stereotypical Black woman who was viewed as happy and content serving in the homes of white families and taking care of white children.

Nonetheless, the failure of several economic sectors during the 1920s meant that African American women did face increased competition for domestic positions from white women. White women servants were more prestigious for employers than black women. As more competition arose in the job market, wages decreased, and, since no union existed for female domestic workers, they were unable to reverse the trends for lower wages and longer hours. African American women who were not in domestic work mainly worked in agriculture or agriculturally-based manufacturing during the 1920s. Nearly 40 percent of Black women worked in agriculture in 1920 and this dropped significantly to 26 percent by 1930, as the agricultural depression took its toll. Women in manufacturing, who mainly worked in tobacco-packaging plants in the South maintained their numbers during the 1920s, at around 7 percent of the Black female work force.

Employment patterns in Florida differed from those found in the rest of the country. Agriculture was still dominant for African American men, but more worked in agricultural industries rather than directly as farmers. The census for 1920 (see figure 4) showed more African American men in Florida working in manufacturing than nationwide—33 percent as opposed to 26 percent. In part, this was due to the booming turpentine and lumber industry. This highly mobile industry that laid waste to the southern Piney Woods, became fully entrenched in Florida in the early twentieth century, generating a significant portion of the lumber for the nation. The bountiful stands of pines supported an abundance of turpentine stills and lumber mills throughout northern and central Florida that attracted African American workers. Many African American men worked in the lumber industry seasonally. Half of the year they labored on their own independent farms, and depended on work in the lumber industry to earn extra money.

The other main industry of Florida was citrus. Citrus began to gain traction in the late 1800s. Wealthy northerners like Henry S. Sanford bought large plots of lands throughout central and south Florida to pursue an interest in citrus crops. With the construction of railroads, the citrus industry boomed, and independent orange growers established small groves throughout the Florida Citrus Belt. African Americans seasonally picked fruit in the large citrus groves as well as harvesting fruit from their own smaller groves. Some worked within the industry as packers or truck drivers, and, therefore, would not have been designated by the census as working in agriculture. The industry moved away from small farms, and into a corporate-run agribusiness during the late 1920s as growers were hit by a number of natural disasters, including the infestation of the “Medfly” that infected nearly 80 percent of Florida’s citrus crop in 1929.

Despite working in the orange groves, a smaller percentage of men worked in agriculture in Florida, than in the nation and this declined from 40 percent in 1920 to 33 percent in 1930 (see figures 4 and 6). African American men who worked solely in agriculture often owned small independent vegetable farms and grew crops like tomatoes, cucumber, celery, potatoes, cotton, and peanuts. The decline in agricultural work in Florida reflected national trends like the agricultural depression and also the fickle nature of Florida’s weather. For example, the September 1926 hurricane caused 1.31 billion dollars’ worth of damage. More African Americans men worked in the domestic field in Florida through the 1920s than throughout the country at 11 percent.

The employment picture for African American women in Florida was like the rest of the nation despite a lower agricultural and manufacturing presence (see figures 5 and 7). The dominance of domestic service was even more pronounced, with 75 percent of Black women working in this sector in 1930 as opposed to 63 percent nationwide. While the 1920s was bad for some economic sectors, others did extraordinarily well, resulting in prosperity for many. More people had disposable incomes, more people traveled, and tourist destinations needed more hotels, restaurants, and employees to cater to them. Many African American women were employed in this sector, although, despite burgeoning demand, they still faced the long work hours with little pay.

A substantial percentage of black women in Florida worked in agriculture, although less than nationwide. These women, like Black men, were concentrated on small, independent farms or as sharecroppers and renters. In either capacity, they were part of the nation and state’s underclass. In line with the nation, few African American women worked in manufacturing, with the percentage falling from seven to five during the decade.

During the 1920s, employment opportunities in Winter Park were largely driven by Florida’s tourist boom. This was not unique to Hannibal Square. Other Florida towns like St. Augustine, Sarasota, and St. Petersburg thrived off a tourist economy, enticing seasonal visitors with elaborate festivals, serene beaches, and other attractions. African American men in Hannibal Square had different employment opportunities than many agriculturally based cities throughout the nation as a whole or in Florida. The decade showed a distinct drop in the number of men in agriculture (see figures 4 and 6)—from 25 percent in 1920 to 8 percent in 1930. Meanwhile, the number of African American men working in domestic service remained consistent at around 33 percent, a much larger percentage than in both Florida and the rest of the United States. These numbers reveal the different employment prospects that the tourist-based economy afforded African American workers. Instead of working as farmers year-round, they worked as gardeners, porters, or chauffeurs for the wealthy white Winter Park residents. For example, Haskell Shumate’s move to Hannibal Square saw him change occupations. In 1920, Shumate was working on a rented farm in Greenville, South Carolina. By 1930, he moved to Hannibal Square. By the end of the decade, he was a truckdriver for a store, probably, Shepard and Fuller, a local white general store located at the junction between Park Avenue and Morse Boulevard, which employed him two years later as a porter.

Other African American men worked in the booming citrus industry of Winter Park, as more packing companies, such as Lake Charm Fruit Company and Tree Gold Packing Company, were established in Central Florida to capitalize on the market of northern visitors who wanted to ship a little sunshine back home. Central Florida area became the hub of the citrus industry throughout the 1920s as growers moved South to avoid the colder areas of northern Florida. This was, in part, to prevent another economic disaster like one that occurred from the Great Freeze of 1894. Thus, these companies expanded and folded the workers of Hannibal Square into the “Big Citrus” industry. The Lake Charm Fruit Company, for example, began to buy large plots in the late 1920s. The Orlando Sentinel noted in 1928 that the company had “recently purchased from Mr. C.S. Lee” a plot of land “located across the railroad tracks from their packing house.” Such companies offered African American men work as both pickers and packagers.

Employment for African American women in Hannibal Square was even more skewed than that of men (see figures 5 and 7). Through the 1920s, an overwhelming 95 percent of working Black women in Hannibal Square were employed in domestic work. The wealthy tourist base of the town’s economy made more domestic jobs available than elsewhere. For example, in 1920 Gussie Morton lived with her husband and son, Oscar, in Jacksonville, Florida. Morton was a cook, and the family rented a room. By 1930, Morton was a servant in Winter Park and owned a home in Hannibal Square, valued at $1,500, where she lived with Oscar. Through the 1930s, although Morton changed place of employment, she always remained a maid or cook. By 1935, her son had attended college—a rare achievement for an African American—and was working as a chauffeur. Ten years later, she was living with Oscar and his wife, Shirley, and their children. Morton’s experience highlighted the plenitude of employment in domestic service available in Winter Park and its relatively lucrative nature, at least in comparison to other employment options available to African American women.

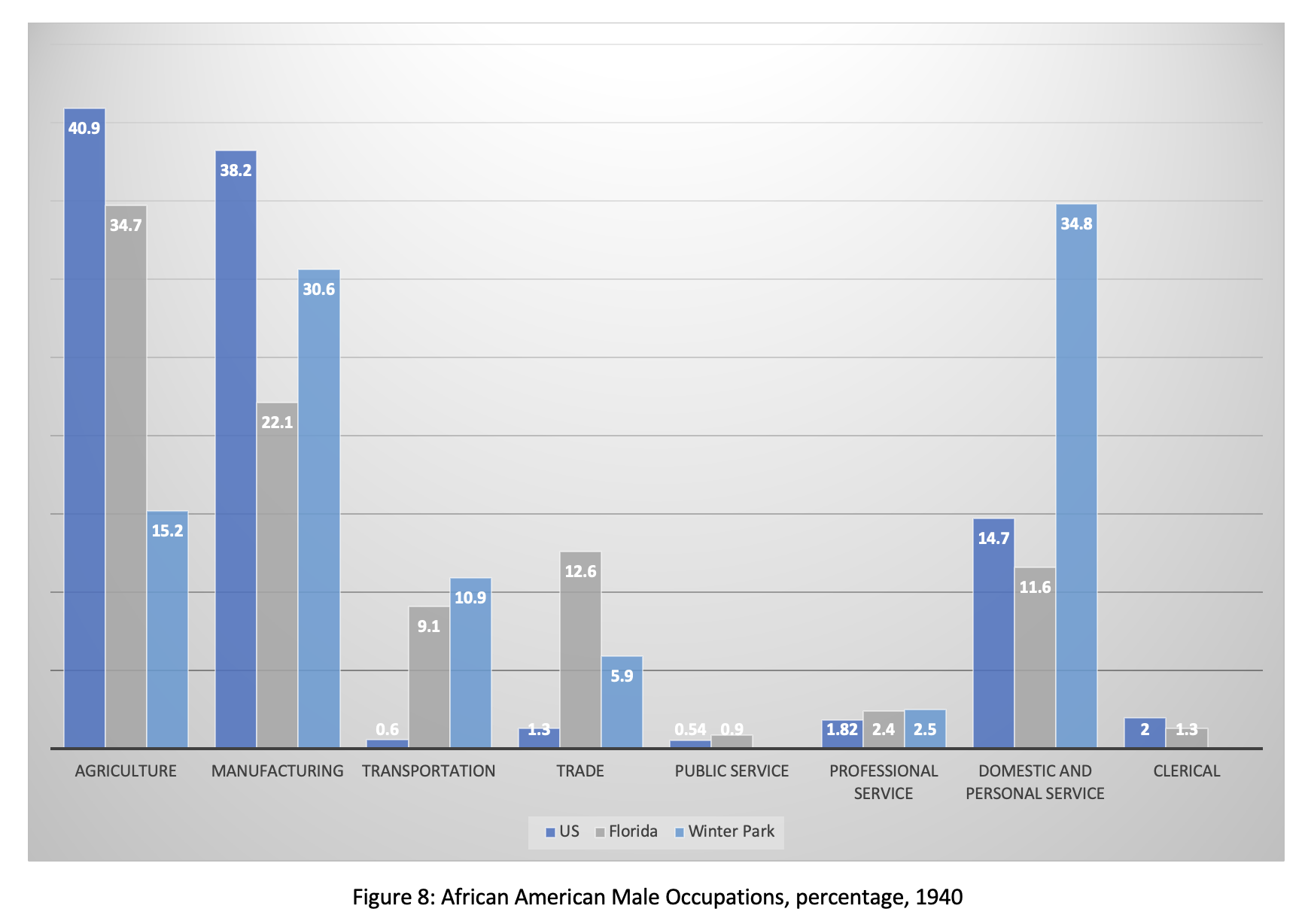

Overall, throughout the 1920s, Winter Park experienced a tourism boom that led to a growth of its African American population in Hannibal Square. Incoming migrants were attracted to the possibility of domestic work, and the growing citrus industry. This shifted, to a certain extent, after 1929, when the stock market crash and the subsequent Great Depression strained all sectors of the US economy and made life even harder for those on the margins. The Great Depression affected African American employment, although not always in ways that was represented in the census. The percentage of African American men working in agriculture stayed about the same as in the 1920s (see figure 8). However, average wages for farmers dropped from $1.60 per week in 1925 to $1.20 in 1932. The federal government attempted to alleviate poverty by easing the hardships of farm owners, but this hurt farm laborers in the process. The federal government paid farmers to reduce crop production, hoping to encourage a rise in prices. This led to more laborers falling into deeper poverty as they were often laid off from their jobs as landowners reduced production. Often these laborers migrated to large cities, and the number of African American men in manufacturing rose from 25 percent in 1920 to 26 percent in 1930 to 38 percent by 1940. The number of black men in domestic work also increased in the 1930s slightly, rising 3 percent, reflecting the growing difficulty to find employment.

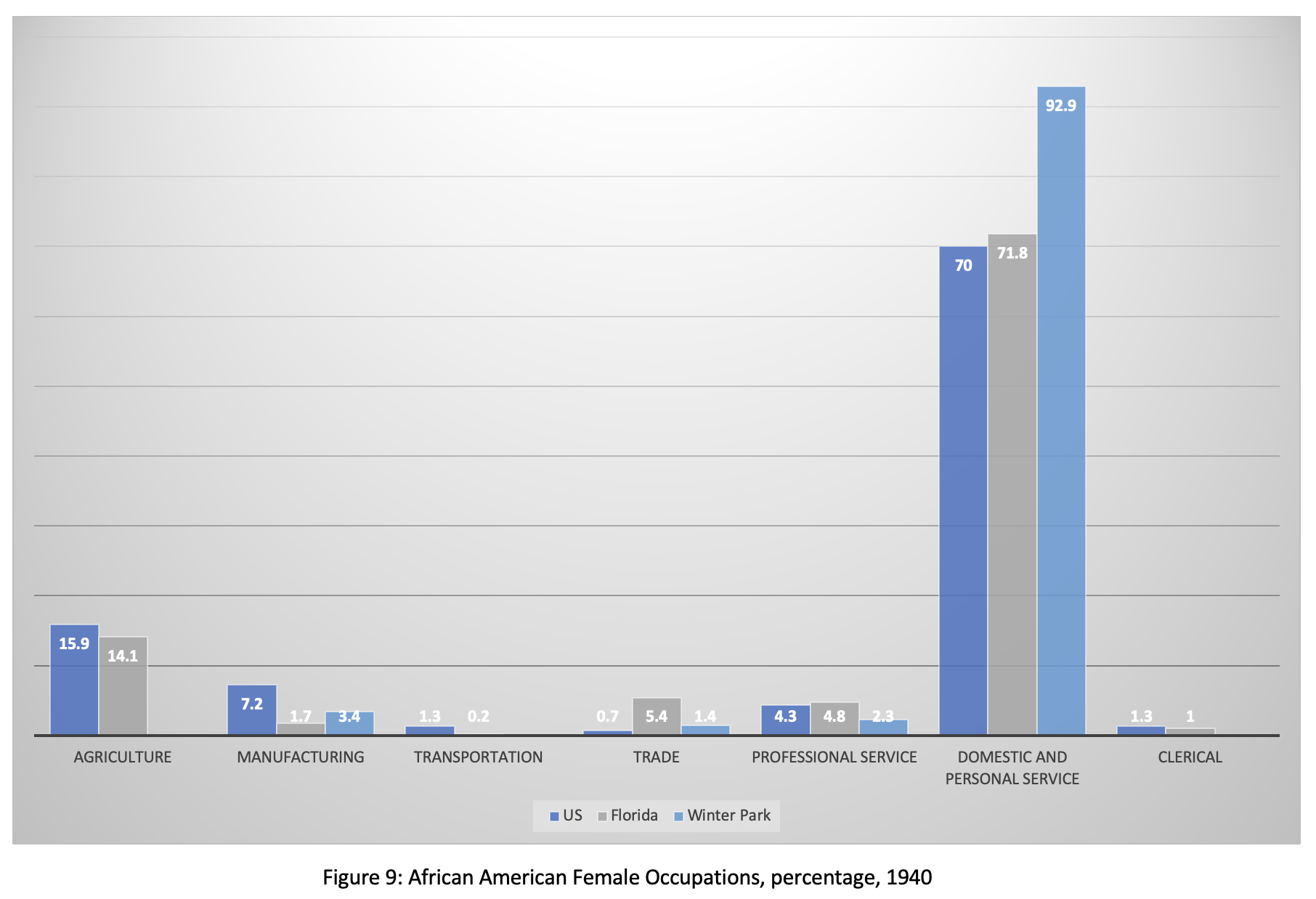

The number of African American women in the United States employed in domestic work also increased during the labor crisis of the 1930s, reaching 70 percent by 1940 (see figure 9). The numbers of African American women in agriculture continued to fall, reflecting the two-decades old crisis in that sector. Like African American men, Black women continued to migrate from rural areas, particularly in the South, to find jobs, often in domestic work, in cities.

![Susie [no last name provided], who lived in Hannibal Square, was a domestic worker at Rollins College when this photograph was taken in the 1930s.](images/a2_img3.jpeg)

Despite the availability of domestic work for African Americans during the Depression, the nature of that work changed, and working conditions declined in the face of national economic hardship. Without unions and with high competition for jobs, African American domestic workers often exchanged their work for a pittance, such as meals or articles of clothing. Poverty persisted for female African American domestic workers throughout the 1930s.

The experiences of Black male workers in Florida did not always follow national trends. The number of Black men in manufacturing decreased during the 1930s, dropping from 32 percent in 1930 to 23 percent in 1940 (see figure 8). This is most likely because African American men were often the first to be laid off. Additionally, the overcutting of trees in the Piney Woods reduced turpentine and lumber production. In comparison, the number of Black workers in agriculture increased slightly from 33 to 37 percent, which perhaps speaks to the continued expansion of settlement along the peninsula.

Florida Black women also found their employment opportunities not fitting neatly into national patterns. The number of Black women in domestic service decreased slightly during the 1930s, dropping from 75 to 73 percent (see figure 9). Many of the domestic workers in Florida serviced the tourist market, which shrank nationally during the Great Depression. However, the number still remained higher than the national average, demonstrating that the ill effects of the financial crisis were not evenly distributed.

The continuation of a strong tourist economy and the subsequent need for domestic workers is evident in the 1940 census data for Hannibal Square. The number of Black men working in domestic work increased from 31 to 35 percent by 1940 (see figure 7). Additionally, although agricultural employment remained static for Black workers nationwide, in Hannibal Square, agricultural opportunities increased. The number of Black men working in the industry rose to 15 percent by 1940. This was probably due to the arrival of new citrus companies in the area. The biggest of these was the Gentile Brothers, who opened an orange-packing factory in 1937 on Park Avenue, directly next to the railroad line for easy access to national markets. Joe B. Arnold was one of the many workers who migrated to Hannibal Square to work in the citrus industry. In 1930, Arnold was a farmer in Greenville, South Carolina. By 1940, he had married his wife Martha and moved to Hannibal Square where they rented a house on Rear Street. By 1942, he was working the Gentile Brothers factory.

While the number of women working in domestic work in Winter Park slightly decreased to 92 percent during the 1930s, the occupation remained predominant (see figure 9). The slight decrease was most likely due to a national decline in tourism. Jance L. Battle was one of the African American women for whom finding work was difficult during the Great Depression. In 1930, she was an employed servant, but throughout the decade, city directories reveal her struggle to retain work. Jumping from a servant, to a cook, to a maid and then eventually listed as unemployed on the 1940 federal census, Battle’s work history was reflective of many during the Great Depression.

The general affluence of the Winter Park community helped maintain African American retention and employment in Hannibal Square through the Great Depression. Through even the height of the Depression, the businesses of Winter Park continued to promote the wealth and luxury that its white residents expected. For example, in 1934, the Winter Park Topics ran an advertisement for a home on Morse Avenue, priced at $16,000. The paper boasted a house with “gas, electricity, water, and automatic hot water system. Servant’s porch,” the landscaping as “among the finest in point of natural beauty and landscaping in the city” and situated in a neighborhood “surrounded by handsome and costly residences and fronts upon palm lined avenue.” The unusual affluence of the community supported local businesses and the African Americans who worked for them even in the depths of the Depression. For example, Arthur Straughter was born in Hannibal Square in the 1890. By 1917 he was a laborer for the M. J. Darling Company, a local business. Straughter clearly had connections or talent or both because, in 1920, he was the manager of a pool room, and by 1928 he bought his own ice cream parlor on New England Avenue. He and his wife kept the business going throughout the Great Depression, and into the 1940s, which reflects on a certain level of disposable income circulating in the community despite the national economic crisis.

African Americans living in Hannibal Square had different employment opportunities than those found through the rest of the United States and Florida. The tourist-based economy and the wealthy residents, along with the booming citrus industry provided a substantial stream of work not comparable on a state or national level. This steady source of employment attracted African Americans to the city throughout the interwar years and helped them weather the economic Stroms of both the 1920s and 1930s.

The different nature of black employment in Winter Park created a close—if definitely unequal--relationship between the white and black neighborhoods in Winter Park/Hannibal Square, which was manifestly different from racial relationships elsewhere in the United States. The small size of Winter Park limited both the size and variety of its minority community. Large urban areas around the country attracted a wide variety of racial and ethnic groups that created vibrant internal communities, independent of the white population. In Los Angeles, for example, after the Southern Pacific Railroad connected California to the rest of the nation, migration rates inclined throughout the early 1900s. The labor of the railroad industry attracted both Chinese and Mexican immigrants, along with African American migrants, creating a multiracial city with strict neighborhood boundaries between the white and non-white communities. In New York City, Harlem had become a big enough black community by the early twentieth century to have a thriving middle class, complete with progressive activism. Hannibal Square had black businesses and an African American community, but its small size and the domestic work of most if its inhabitants meant it was inextricably linked to white Winter Park.

Relationships between white and black communities elsewhere in the United States were often defined by antagonism around housing and jobs. In many big cities, covenant laws severely restricted black living space. Los Angeles, led by the California Real Estate Association, used covenant laws to control where African Americans could purchase property and live in the city. The Chicago Real Estate Board also adopted the policy of selling houses to African Americans only in blocks that they determined as African American. These laws often led to responses and challenges from black residents. In 1926, African Americans challenged racially restricting covenant laws in the case Corrigan v. Buckley. In that case, the US Supreme Court decided that restriction and enforcement of racially restricting covenant laws was legal and upheld this decision until 1948. Such antagonisms were minimized in Hannibal Square because its founders had platted a sizeable area that was designed for black housing. While still segregated, African Americans did not lack housing nor did they have to fight for it as they did in so many other cities.

Employment was another source of tension in many cities. The interwar years saw a steady increase in African Americans living in urban areas. Indeed, by 1940 nearly half of all blacks in the United States lived in cities. Attracted to the boom in industrial jobs during World War I, many African Americans became embroiled in the labor turmoil of the postwar period. With a contracting economy, African Americans were the first to be fired, increasing their economic desperation. This, in turn, positioned them to be exploited by companies as scabs, used in efforts to break the many strikes that flared across the country in the late 1910s and early 1920s. From the coal mines of Pennsylvania to the stockyards of Chicago, the use of African Americans to break industrial unions worsened race relations and often led to violence, from dynamiting of black dwellings to full-scale race riots. From July 27 to August 2, 1919 in Chicago, for example, the competition over jobs, exacerbated by returning servicemen ended in a riot that left thirty-eight dead, over five hundred injured and more than one thousand homeless.

Racial violence was certainly not unknown in Florida. Only some twenty miles away from Winter Park, a racial violence broke out in the small town of Ocoee in 1920 after a Black man, Moses Norman, attempted to vote. This led to a confrontation between him and the poll workers. After Norman retreated to the home of his friend, July Perry, a mob of angry men, intending to put Norman in his place for challenging the status quo, surrounded the house and a gunfight ensued, leaving two white men dead. The resulting anger spread through the community and a mob of antagonized white men, some of them Klan members, burned the African American section of Ocoee, killing an unknown number of Blacks, and lynched Perry. Within days, most African Americans left Ocoee and avoided the town for many decades. Although the violence centered on the election, Blacks in Ocoee—like those elsewhere in the country—actually represented an economic threat to local whites. One-third of the African Americans in Ocoee owned their own homes and many owned citrus groves as well. Indeed, Norman owned groves worth $10,000. Having such racial violence in such close proximity led the white residents of Winter Park to control the residents of Hannibal Square in a different way to avoid such tensions: paternalism.

African Americans in Winter Park could never challenge or threaten the wealth and status of their extremely rich white neighbors and employers, thus, avoiding economic tensions. At the same time, the physical proximity of the two communities and their economic co-dependence was manifest in paternalism: white Winter Park residents frequently directed their philanthropy to African American institutions in Hannibal Square. For example, in April 1916, the Winter Park Post reported that the Winter Park Women’s Club had realized that that thirty African American caddy boys at Winter Park Links, who were mostly around fourteen years old, had no schooling past 1st grade. The women raised funds “to keep the children regular in attendance” at school, while they continued working. Paternalism between black neighborhoods and their white counterparts was not exclusive to Winter Park. During the Progressive era, urban, middle-class whites throughout the South, focused on uplift in their local Black communities, with varying degrees of cooperation from African Americans. Reflecting a deep commitment to the Lost Cause and romanticized notions of slavery, more progressive southerners sought modest improvements in African American education, health, and housing. However, the paternalism exhibited in Winter Park differed from much of the rest of the South in two important ways. First, many white Winter Park residents were snowbirds or permanently relocated northerners, which rooted their actions in practicality rather than romance. And, second, while all white philanthropy can be interpreted as self-serving, that of the white Winter Parkians was more obviously so.

One of the biggest recipients of white philanthropy in Hannibal Square was its black nursery—a vital service to allow black women to work long hours in white homes. Rachel Lester was a black nurse who came to Hannibal Square in the early 1920s from Maitland, a small adjacent city. Lester attended nursing school in Savannah before returning to Florida in the mid- 1920s and establishing the Welbourne Avenue Nursery and Kindergarten. During the Great Depression, Lester retained her daycare, accepting large amounts of charity from the Winter Park Woman’s Club. According to the treasurer of the Woman’s club, Mrs. Bonties, “the nursery is supported entirely by donation.” In 1937 Lester partnered with the Winter Park Day Nursery Association, which was a branch of the Winter Park Community Fund, to expand her nursery with a new building. Indeed, the fund also helped feed children who were unable to bring meals for themselves. In the late 1930s, students at Rollins College established the Rollins College Interracial Council, which also engaged in local philanthropy, including donating funds to the nursery. The nursery still operates today, but its survival during the interwar years was due to both perseverance from Lester and white charity—in effect, a hidden cost whites paid to ensure their Black labor force.

The circulation of wealth in Hannibal Square led to the growth of a Black middle class. Residents established businesses that continued throughout the interwar years. Payton A Duhart, for example, was a tailor who owned a business in Thomasville, Georgia, in 1910. He decided to move with his wife and two children to Hannibal Square. By 1922, Duhart established a tailor shop at 243 New England Avenue, which he maintained until 1936, when perhaps due to Depression-induced hardships, he started working as a janitor at a local theater. Paul Laughlin followed a similar path. Laughlin was born in 1888 in Hancock, Georgia, and worked on his family farm. During the 1910s, Laughlin worked for a spell as a butler for Ralph Peter in Garden City, New York. In 1923, Laughlin married a woman named Chanie, and together they established the Laughlin Hotel in Hannibal Square at 444 West New England Avenue. Though acting more as a large boarding house, than a hotel, the Laughlin’s business survived the Great Depression, housing a handful of patrons, serving the African American community of Hannibal Square. His wife, Chanie, conducted integral work to help race relations between Winter Park and Hannibal Square. Into the 1950s, she formed the Benevolent Club for women and eventually established the DePugh Nursing Home on 550 W. Morse Avenue, with the help of white philanthropist, R. T Miller. The Laughlins’ story highlights the opportunities for business ownership in Hannibal Square and the influence of white philanthropists. Other African Americans established grocery stores, ice cream shops or tailor shops to service both African Americans in Hannibal Square and in some cases, the wealthy white Winter Park residents. The presence of white philanthropy paired with black perseverance led to a self-sufficient and growing Black community in Hannibal Square.

Different patterns of in migration, employment and paternalism created a unique African American experience in Hannibal Square throughout the interwar years. Fueled by larger national trends like the Great Migration, the influx of black residents to Hannibal Square consisted of small-to medium sized towns in the Southeastern United States. African Americans compelled to move from the Southern United States due to economic stifling, and increased racial violence went northward, while others came to a small wealthy community in central Florida. Hannibal Square attracted African American residents because of employment in the domestic industry and the citrus industry, providing different employment opportunities than other southern towns. The number of African Americans in Hannibal Square retained and grew throughout the interwar years because of the relationship with white Winter Park. The strong self-serving paternalistic relationship created an environment for more business ownership through white philanthropy, and the development of a black middle class. This allowed for African Americans in Hannibal Square to develop a self-sufficient community, with a connection to Winter Park. These factors helped to strengthen the endurance of the Hannibal Square community in preserving its culture, history, and stories.

eFHQ is a collaboration between the Florida Historical Society and the Florida Historical Quarterly, as well as the Department of History and the Center for Humanities and Digital Research at the University of Central Florida.